In the early decades of the automobile, engineers took on the challenge of adapting aeroplane design to cars. Many of these streamline cars were done just for style, but Karl Schlör had something else in mind. His late 1930s creation, the Schlörwagen, was more aerodynamic than most cars today.

Car aerodynamics date back over a century. Back then, engineers, inventors and designers sought to improve the blocky automobile by taking inspiration from aviation. You may be familiar with the Stout Scarab or the Tatra 77. But none of them are quite like the 1939 Schlörwagen prototype.

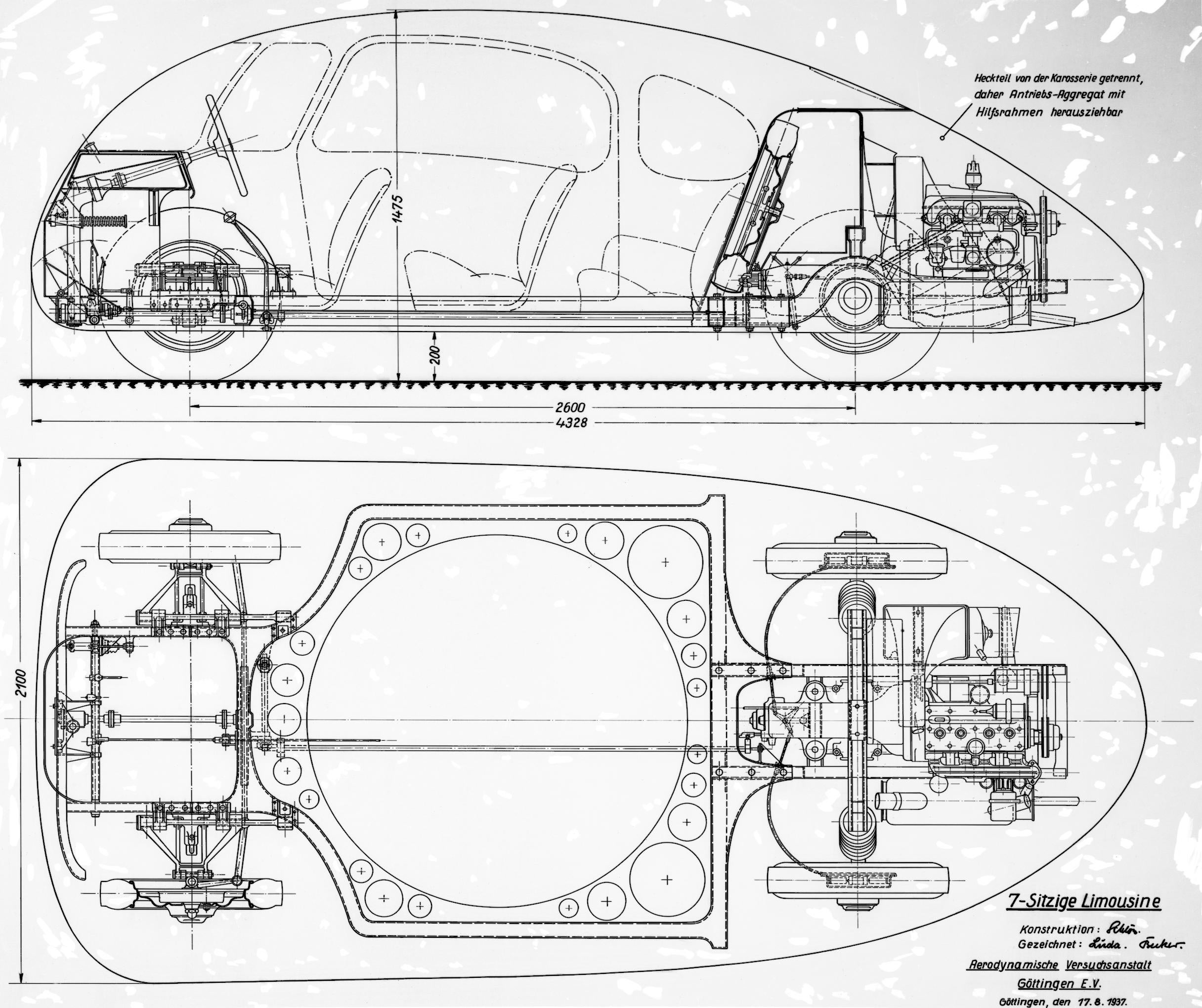

Karl Schlör was an engineer at the Aerodynamic Research Institute (Aerodynamischen Versuchsanstalt; AVA), an organisation called the German Aerospace Centre today. He had two goals in mind for an aerodynamic car: to reduce fuel consumption in a vehicle with enough room for the whole family. Schlör chose for the shape of his car to emulate the profile of an aeroplane wing, from German Aerospace Centre:

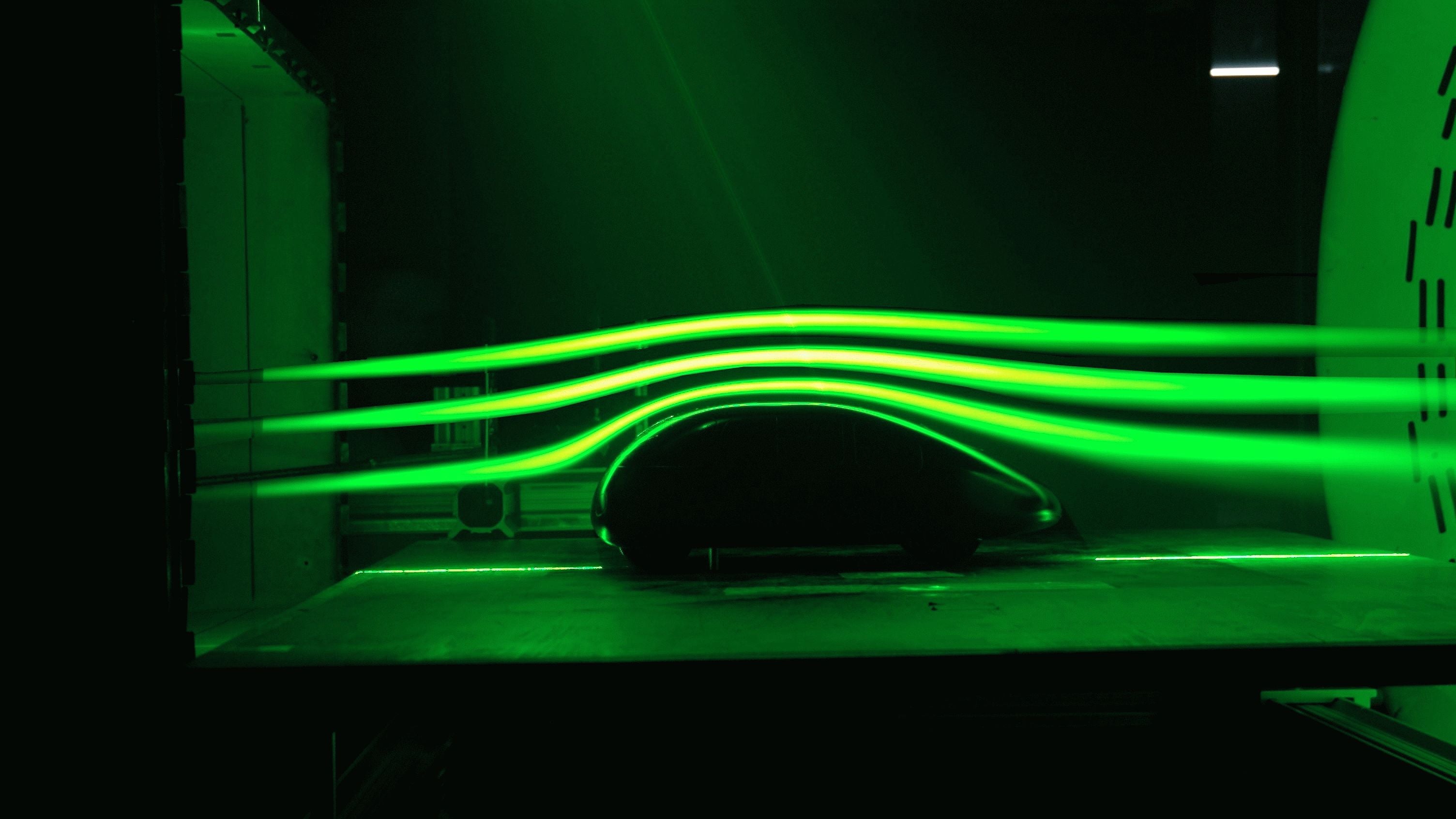

In selecting the basic shape of the vehicle, Schlör chose two aircraft wing profiles that offered particularly low drag. In a way, the vehicle resembles one half of a drop of water, which was probably the reason for its nickname, the ‘Göttingen Egg’. “Basically, the Schlörwagen is a wing on wheels,” explains Andreas Dillmann, Head of the DLR Institute of Aerodynamics and Flow Technology.

And to make sure that the vehicle’s aerodynamics were disturbed as little as possible, the body was kicked out far enough to allow the front wheels to turn full-lock inside. The car was built on the chassis of a Mercedes-Benz 170 H and when all was said and done the car had a drag coefficient of just 0.186.

While it was aerodynamic, it was also pretty large. The car measured in at 4.33 m long and 2.10 m wide. It also came in at 250 kg heavier than the donor 170 H.

To put that into perspective, the Mercedes-Benz EQS is touted as the most aerodynamic production car right now with 0.20. Volkswagen’s XL1 matches the Schlörwagen at 0.186, but as German Aerospace Centre notes, that car doesn’t seat seven like the Schlörwagen.

In 1939, the Schlörwagen was run through its paces on the then newly constructed highway near Göttingen. While a stock Mercedes-Benz 170 H could achieve 105 km/h on the highway, the Schlörwagen could do 135 km/h. And despite the extra size and weight, it achieved a 20 to 35 per cent reduction in fuel consumption over the Mercedes.

After the tests, the car was taken to the 1939 International Motor Show (IAA today) where it surprised crowds with its unconventional appearance.

Why did it never reach production? According to the German Aerospace Centre, the car’s aerodynamics came at the expense of safety. Not only was the car difficult to drive but a strong crosswind could sweep it right off of the road.

The centre believes that a modern interpretation of the car could be built with the help of electronic driver assistance.

The outbreak of World War II shelved any further development of the car, and the Schlörwagen would never be more than a prototype. It was seen again in 1942 after a 130 horsepower Russian aircraft engine was fitted to the back and tested.

The Schlörwagen remained in the hands of AVA Göttingen until August 1948. The car was preserved, but in damaged condition with missing parts. Sadly, Schlör would never see his creation again as in the same year, the British Military Administration wouldn’t release the car to a tow truck. It is believed the car was scrapped.

The car lives on today in scale models and photographs as proof of what engineers could do, even over 84 years ago.