Over 20,000 galaxies glimmer in this sweeping view of the sky between the constellations of Pisces and Andromeda. But more than just an arresting sight, the view has helped astronomers determine what sparked the Epoch of Reionization, the period when the opaque universe gave way to the transparent one.

The earliest days of the universe were cloaked in a dense gas that limited the amount light could travel through it. During the Epoch of Reionization — when the universe was about 400 million to one billion years old — the gassy universe began to clear up, until the entire thing was transparent to light.

The Epoch of Reionization was thus crucial for our own ability to see what the heck happened. The Square Kilometre Array — the soon-to-be largest radio telescope in the world — is making the enigmatic time period its focus.

It’s now been some 13.7 billion years since the Big Bang, and Webb has the perception to peer back to those earliest eons to understand exactly what changed.

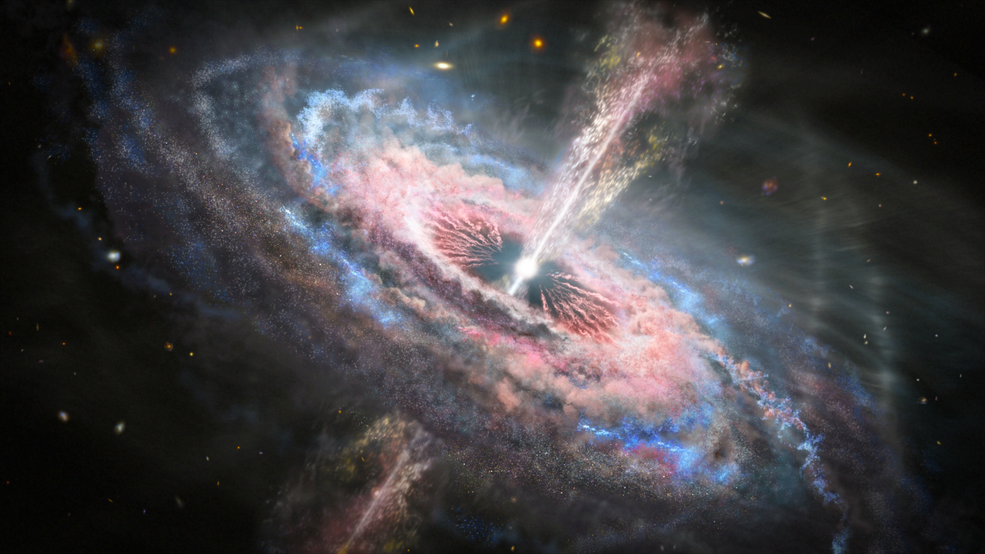

At the centre of the above image lies a pinkish light source with six diffraction spikes (artifacts of Webb’s imaging). The light source is the quasar J0100+2802, an extraordinarily bright galactic nucleus that lights up gas between itself and Webb.

The composite image includes several exposures by Webb’s NIRCam instrument, seen through different filters; all exposures were taken on August 22, 2022. Our website can only handle a smaller version of the image; you can see it in its 127-megabyte glory here.

A team of astronomers — vis-a-vis Webb — used the quasar’s light to study over 100 galaxies from the universe’s first billion years, focusing on 59 that sit between the quasar and the telescope.

We expected to identify a few dozen galaxies that existed during the Era of Reionization–but were easily able to pick out 117,” said Daichi Kashino, an astronomer at Nagoya University, and lead author of one of the papers. “Webb has exceeded our expectations.”

The researchers compared the Webb data with previous observations of the quasar taken by the Keck Observatory, the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope, and the Las Campanas Observatory’s Magellan Telescope.

Their findings were published in three separate papers, out today in the Astrophysical Journal. One paper focused on evidence for reionization driven by the young galaxies, a second described the spectroscopy of the stars and gas in the galaxies, and a third focused on the quasar central to the entire investigation.

The researchers found that regions around the galaxies were bubbles of transparency, suggesting that the galaxies themselves were involved in the reionization of the universe.

“As we look back into the teeth of reionization, we see a very distinct change,” said study co-author Simon Lilly, an astronomer at ETH Zürich in Switzerland, and the leader of the research team, in a Space Telescope Science Institute release. “Galaxies, which are made up of billions of stars, are ionizing the gas around them, effectively transforming it into transparent gas.”

Light from the quasar showed precisely where it was being absorbed by gas (meaning a region had not yet reionized) or continued to travel (meaning the area was more transparent.) The transparent regions around galaxies were generally about 2 million light-years across, according to the same release.

The transparent regions surrounding galaxies swelled and combined, eventually rendering the entire universe transparent.

One outstanding item Webb alone cannot decipher is how the luminous quasar became so large so early in the universe’s evolution. J0100+2802 is about 10 billion times the Sun’s mass. How black holes evolve remains a tantalising question, as astrophysicists have yet to understand how supermassive black holes become just that, and why there appears to be so few intermediate-mass black holes (while there’s a plethora of stellar-mass and supermassive ones.)

Webb is on something of a tear when it comes to deep field imaging of ancient galaxies; just last week a deep field with twice as many galaxies (45,000 in total) as the above image was released.

Webb’s gaze is unflinching, and with scores of researchers poring over its data, the evolution of the early universe — once a murky mess — is becoming crystalline.