A group of common cold viruses may be able to cause a life-threatening, if rare, blood clotting condition, recent research suggests. A team of scientists in the U.S. and Canada have recently found evidence linking the viruses to two cases of the condition, in a child and an adult. At this point, however, much remains unknown about the connection, including the actual risk of this complication following infection.

Some time ago, doctors at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine came across a peculiar case. A five-year-old boy had become hospitalized with a dangerous blood clot in the brain’s venous sinuses and a severely low count of platelets in his bloodstream—platelets being the small cell fragments that help stop bleeding by forming clots. From the looks of it, the boy seemed to have the classic signs of an anti-platelet factor 4 (PF4) disorder, a condition caused by antibodies attacking the PF4 protein produced by platelets. But the patient had no reported exposures to known triggers of these disorders, such as the anticoagulant medication heparin. Testing did still appear to support the diagnosis. Unfortunately, the boy succumbed to his illness.

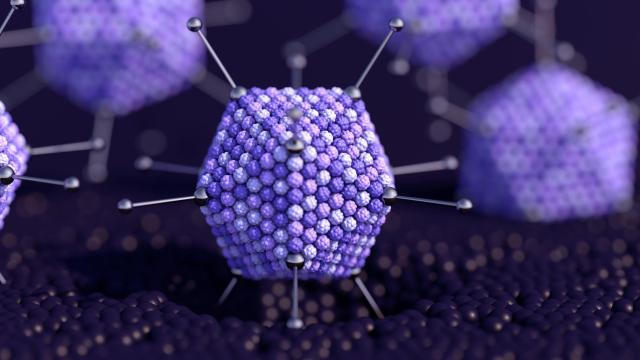

Just before the child’s hospitalization, he had been diagnosed with an adenovirus infection, which typically causes mild respiratory and/or gastrointestinal illness. His doctors also knew that another anti-PF4 disorder had recently been discovered—a very rare complication caused by certain covid-19 vaccines that used a neutered adenovirus as its delivery agent (in the U.S., this only includes the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, which saw little uptake and is no longer available). The doctors reached out to other experts in the field, wondering if anyone else had ever linked adenovirus infection itself to this complication, but found nothing. As luck would have it, though, they were soon contacted by a doctor (and UNC alum) in Virginia who was treating an adult with similar issues.

The adult, a 58-year-old woman, had developed multiple blood clots, low blood platelets, and several clot-related health problems, including a stroke and heart attack. Like the boy, she had contracted adenovirus days before the trouble began, and she had no exposure to other known triggers for an anti-PF4 disorder. Testing of the boy’s and the woman’s blood then confirmed the presence of anti-PF4 antibodies—antibodies that bore a close resemblance to the antibodies seen in cases of the clotting condition found in vaccine-injured people.

The team’s work, published last month in the New England Journal of Medicine, provides clear evidence of a newly discovered anti-PF4 disorder, the authors say, one closely tied to adenovirus infection.

“This adenovirus-associated disorder is now one of four recognized anti-PF4 disorders,” said study author Stephan Moll, professor of medicine at UNC’s Division of Hematology, in a statement from the university.

Like other anti-PF4 disorders, this condition is almost certainly rare, though how rare is still unknown. Other key questions include whether other viruses can cause this complication and how exactly it happens. The authors do note that research elsewhere has shown that PF4 can sometimes bind to adenoviruses, which could be one crucial factor.

More studies will be needed to better understand this link, though the team believes their research can already help doctors who come across these cases in the future.

“We hope that our findings will lead to earlier diagnosis, appropriate and optimized treatment, and better outcomes in patients who develop this life-threatening disorder,” Moll said.