A silky shark with a chunk taken out of its dorsal fin regrew much of its lost appendage, according to photographs taken of the fish nearly a year apart. Research describing the elasmobranch’s recovery is published in the Journal of Marine Sciences.

Silky sharks (Carcharhinus falciformis) are commonly found off the coasts of all continents but Europe and Antarctica, according to the Florida Museum. Though they generally inhabit the open ocean, the sharks are also found in shallow waters near the coasts. That causes them to come into contact with humans. Silky sharks are vulnerable due to over-fishing, a blight affecting most of the shark and ray species worldwide, notes the Shark Trust.

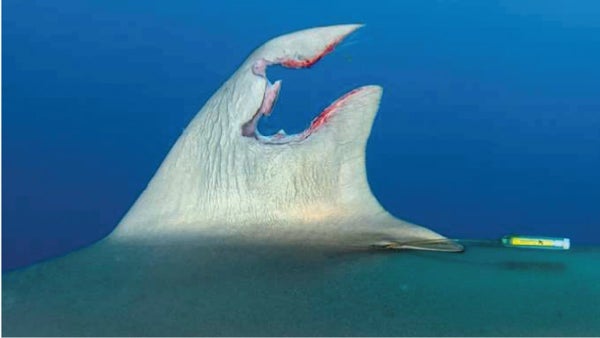

The recently studied silky shark individual was spotted in July 2022, off the coast of Florida. It had a large slice taken out of its dorsal fin, the prominent fin on a shark’s back. The missing tissue was where scientists had installed a satellite tag tracker a month earlier. The tags only transmit data when above the surface; since the team stopped receiving data from the shark several weeks after it was tagged, the tag presumably was damaged or sunk.

However, 332 days after the wounded shark was photographed, divers spotted the same shark, identifiable by the NOAA dart tag which remained attached to the base of its dorsal fin. There was no longer an open wound in the fin. Chelsea Black, a researcher at the University of Miami and the paper’s author, wrote that “it appears that the top portion of the fin fused together with the bottom and tissue filled in the middle to form the newly shaped dorsal fin.”

Black concluded that the shark was caught but then returned injured to the ocean. Whatever the reason for the shark being caught—a mistake or something more nefarious—the animal’s tag was crudely removed with a sharp object, Black wrote.

The injury had healed to 87% of the fin’s original size, according to the paper. Black calculated that the wound was likely closed by 42 days after the injury, consistent with healing rates in other elasmobranches, the group of fish that includes sharks, rays, and skates.

Had the fin been fully amputated, the paper noted, it probably would not have regrown. But in this case, enough of the fin remained that the shark was able to bridge the gap with a combination of regenerated tissue and scar tissue.

While the findings are a unique look at how silky sharks heal, the paper notes that the lost satellite tag would have yielded more information. “Not only did the forceful removal of this satellite tag cause traumatic injury to the shark, but it negatively impacts the entire species through loss of invaluable data needed for increased protection,” Black wrote in the paper.

Tracking sharks is a crucial means of studying their migration patterns, breeding, and other aspects of the slippery fishes’ lifestyles. So, please, don’t catch them and slice off the tips of their fins. They may not all be as lucky as this silky shark.