Do not scratch your eyes: the Moon is slowly shrinking, causing quakes on its surface that complicate NASA’s plans for landing Artemis 3, the first Artemis mission that will make a crewed landing on the Moon, and more ambitious missions geared towards maintaining a prolonged human lunar presence.

Yes, there are plenty of tremors on other bodies in our solar system. On the Moon, they’re moonquakes. On Mars, they’re marsquakes, over 1,300 of which were detected by NASA’s InSight lander before the mission ended in December 2022. These quakes aren’t always caused by natural processes: a team that recently scrutinised moonquake data from 1972 found that the seismic activity came from the Apollo 17 lunar lander, not the rocky satellite on which it alighted.

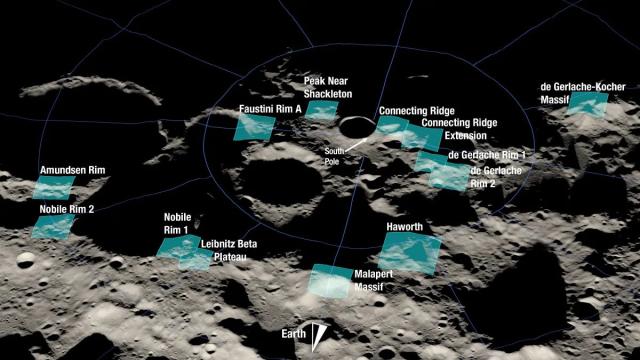

Now, a team of geologists and planetary scientists have focused their sights on the Moon’s south pole, where contractional forces deform the lunar surface. The region is also home to some of the 13 candidate landing regions NASA has selected for the Artemis program, making the seismic activity a serious issue to consider.

The team’s research, published in The Planetary Science Journal, revealed the extent to which the Moon’s south pole is shaped by these seismic events. The study also emphasised the importance of planning around these events when it comes to landing spacecraft on the lunar south pole, especially because the quakes could catalyse landslides of lunar regolith (rocky topsoil.)

“Our modelling suggests that shallow moonquakes capable of producing strong ground shaking in the south polar region are possible from slip events on existing faults or the formation of new thrust faults,” said Tom Watters of the Smithsonian Institution, and the study’s lead author, in a NASA release.

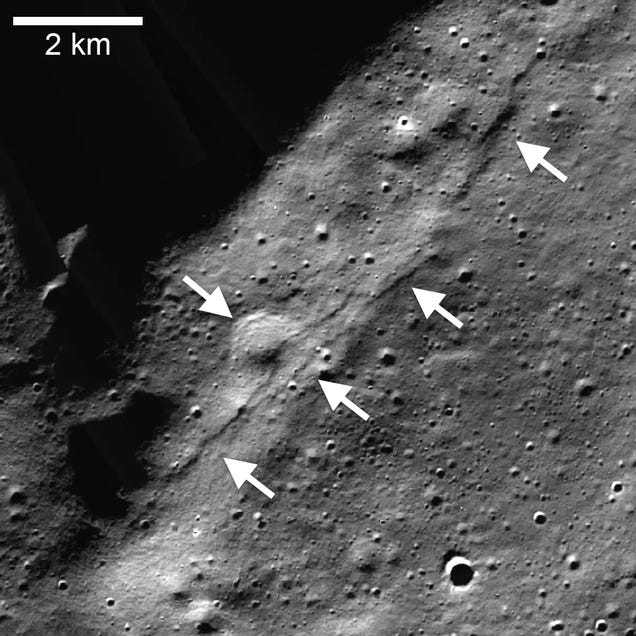

NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) Camera has spotted thousands of young faults on the lunar crust, where forces in the Moon’s interior have either contracted or expanded, creating significant thrust faults on the crust. The contractional forces are caused by the cooling of the Moon’s insides, but also tidal forces exerted by the Earth. These thrust faults create large slopes between areas of different elevation on the Moon’s surface.

Modelling the seismic conditions that may have formed one of the largest scarps in the region—less than 40 miles (60 kilometres) from the pole—found that a moonquake with a magnitude of about 5.3 could have caused the scarp. Such a quake would create “moderate ground shaking” as far as 25 miles (40 km) from the epicenter, the researchers wrote, and moderate to light shaking could be felt as far as 31 miles (50 km) away.

Furthermore, the team found that steeper slopes in the Moon’s Shackleton crater—near one of the candidate landing sites—are susceptible to landslides, and a small tremor is all that would take to catalyse such an event.

“To better understand the seismic hazard posed to future human activities on the Moon, we need new seismic data, not just at the South Pole, but globally,” said study co-author Renee Weber, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, in the same release. “Missions like the upcoming Farside Seismic Suite will expand upon measurements made during Apollo and add to our knowledge of global seismicity.”

Related article: NASA’s Artemis Moon Landing Program: Launches, Timeline, and More

Moonquakes present a significant challenge to NASA’s Artemis program, extending beyond the immediate concerns for the Artemis 3 mission (currently planned for late 2026). These seismic activities may pose a risk to the long-term ambitions of establishing a sustainable and permanent human presence on the Moon. Planned lunar camps, habitats, and essential infrastructure (such as power and communications systems) would seemingly be vulnerable to the destabilising effects of moonquakes, as would be efforts to extract resources from the surface. Artemis is a complex endeavour as it is, but these new findings have the potential to complicate the project even further.

To borrow (and adapt) a quote from John F. Kennedy’s Moon speech, delivered 62 years ago: we do not explore the Moon because it is an easy thing to do. We do it because, despite the hazards of space exploration, it could help us understand the origins of our solar system, and prepare humankind to take the next big leap: to Mars.