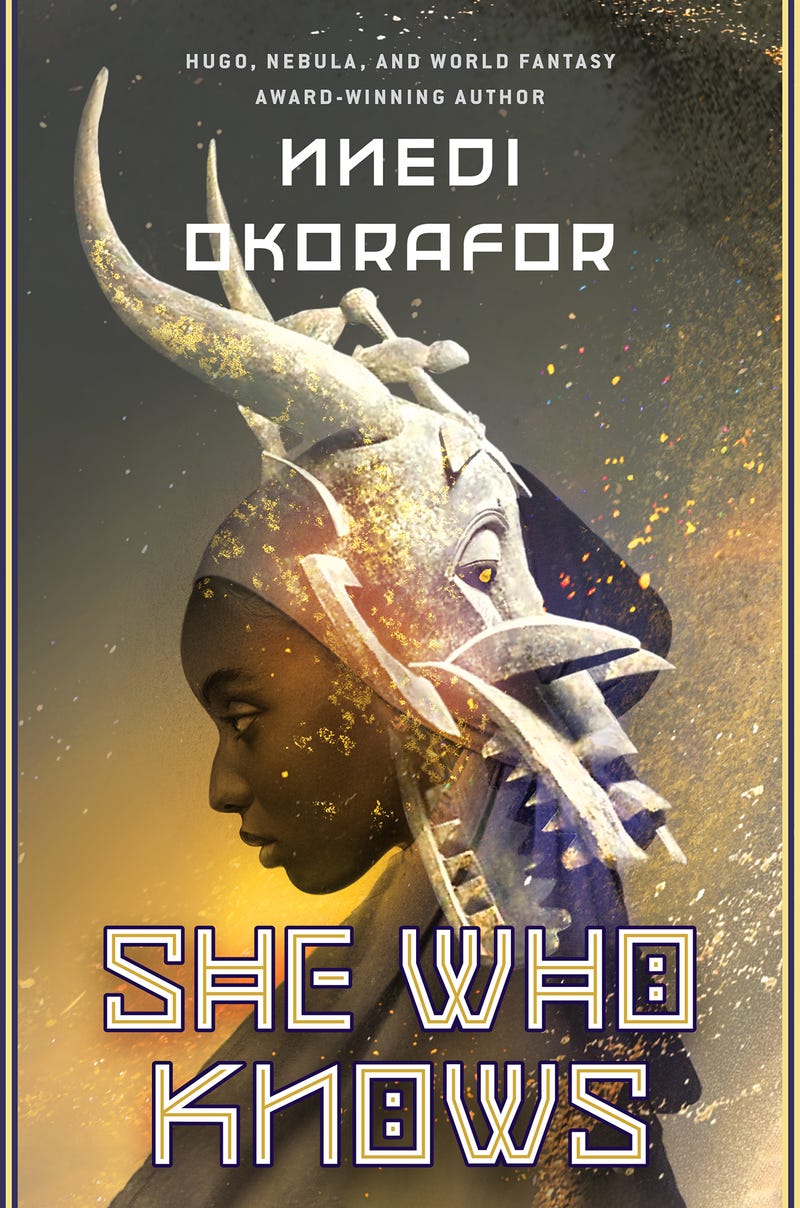

The Africanfuturist world Nnedi Okorafor introduced in Who Fears Death—a book currently in development for an HBO series executive-produced by George R.R. Martin—grows with her new trilogy, She Who Knows. Novella Firespitter kicks off the new series with its release August 20, and io9 has an exclusive look at the cover and the first chapter to share today.

Here are more details about the book’s story, described as “part science fiction, part fantasy, and entirely infused with West African culture and spirituality.”

When there is a call, there is often a response.

Najeeba knows.

She has had The Call. But how can a 13-year-old girl have the Call? Only men and boys experience the annual call to the Salt Roads. What’s just happened to Najeeba has never happened in the history of her village. But it’s not a terrible thing, just strange. So when she leaves with her father and brothers to mine salt at the Dead Lake, there’s neither fanfare nor protest. For Najeeba, it’s a dream come true: travel by camel, open skies, and a chance to see a spectacular place she’s only heard about. However, there must have been something to the rule, because Najeeba’s presence on the road changes everything and her family will never be the same.

Small, intimate, up close, and deceptively quiet, this is the beginning of the Kponyungo Sorceress.

Here’s the full cover—illustration by Greg Ruth, design by Jim Tierney—followed by the excerpt!

Onye Fulu Mmo Di?

[Who Sees a Spirit and Lives?]

If I stood there long enough, I was sure I’d see one of the Old Ones dancing in the distance. That’s how hot it was that day. I brought my portable from my pocket and looked at it. At the top of the screen, it announced it was the hottest day of the year. Then it decided to shut itself down for the next hour to keep from overheating.

It was dusk, yet still boiling hot outside. Not unusual, but a little disturbing nonetheless. A thin shower of rain began to fall and a large brown bird squawked and then took to the air from the neighbor’s roof across the road. The desert is strange.

I was standing there because this was the moment. The beginning. I shut my eyes and took a deep breath, inhaling it all, the fact of it. Through my mouth, to my lungs, to the rest of my body.

I’d just come from my brother’s house, where I’d spent some hours with their new baby who was so fat and cute and happy. I’d been thinking about what it would be like for me in a few years. Now I wasn’t thinking about any of that at all. My mind was full of a new knowledge.

I turned around, opened the door, and went inside to find my parents. I was thirteen years old and I was a girl. Yet I was sure. Absolutely positive. I opened my eyes and paused, rubbing my forehead.

“I can’t believe this,” I whispered. I went inside and found my mother in the kitchen, where she usually was at this time of day.

“Fry those yams, Najeeba,” she said, her back to me. The round slices were on the cutting board and the deep pan of oil on the stove was just starting to heat up. On the other burner was another large pan of sizzling chopped tomatoes, olive oil, smoked aku, sautéed onions, curry, smoked mushrooms, and chili peppers. On the counter behind her, sitting in its own sunbeam on its royal blue ornate plate with the gold flecks embedded into the shiny porcelain was a large cube of salt. The bowl of several stirred eggs was on the counter beside the stove. Mama was making egg stew. I joined her, my heart pounding hard. I opened my mouth to speak. To ask.

Then my father entered the kitchen, grinning. He put his arms around my mother.

“Papa, I want to go this year, too,” I blurted.

My parents stared at me and then my mother turned and looked at Papa. “You’ve told our daughter before me?” she asked.

“No,” he said, looking questioningly at me. “I haven’t told anyone. I was about to tell you right now.”

Mama looked hard at me with her near-black piercing eyes. “What does it feel like?” she asked.

I thought for a moment. I’d never asked Papa, so I had no context to draw from. I said the first thing that came to mind: “Like . . . like the wind is blowing me toward the door.”

Mama’s eyes grew wide and she looked at papa, who also looked shocked. Then she grinned. “I’ve given birth to three boys, not two.”

“Apparently so,” Papa agreed.

Mama hugged me tightly, kissed my cheek, and then she shoved me back toward the now-sizzling yams. But I noticed her eyes had grown wet. She loved her solitude, but she didn’t want me to go. She stepped to the cube of salt and picked it up.

“Salt is life,” the three of us softly recited as she grated some into the bowl of eggs.

My father and I held out our hands and my mother grated some onto them. We rubbed our hands together and then pressed them to our chests. Salt has always been important to humanity, yes. Even here in Jwahir, it’s worth more than most things. But back in my village, salt was sacred to my people. It was life but also culture, self-worth, our purpose for existing.

My mother poured the egg into the sizzling vegetables and began to slowly turn it. Papa sat at the table, looking hard at me as he continued to rub his hands. “You’re sure?”

“Yes, Papa.”

“It’s a week there, a week to the market, a week back.”

“I know,” I said.

“The way is not easy.”

“I know, Papa.”

“The Okeke at the market are camelshit people,” Mama added. “They see us as abominations, even if you are kind. Doesn’t matter that we are all Okeke people. It is the plight of being Osu-nu.”

“I know, Mama.”

“You’ll still have to be kind, but strong.”

I nodded. “Yes, Mama.”

“Is your Abdul strong enough?” Papa asked. Abdul was my camel.

“I will make him so,” I said.

I turned to look at the frying yam as Mama looked to my father and my father to my mother and they did that silent thing they always did. My parents could have a whole complicated conversation without opening their mouths.

My oldest brother Rayan said they spoke through their eyes, but it was more than that. When they talked like this, I always wanted to leave because it just made me feel so . . . not there. Like they’d already shoved me out of the room and shut the door and my body just had to catch up with my spirit. But I stayed where I was, letting the yams brown and then flipping them over. I carefully took them out, stacking them on the cloth-covered plate.

Mama gave the egg stew a few more turns and ladled it all into a large bowl. The stew was fluffy and hot and I had no doubt that it was tasty. With the yams, it was the perfect meal. “Who will maintain our vegetable garden while you’re away, Najeeba?” my mother asked me, preparing a plate of the stew and yams for my father.

“You will, Mama,” I said.

“No,” she said, smirking. “I will pay someone to do it.”

The three of us laughed. Of course she would.

She Who Knows: Firespitter by Nnedi Okorafor excerpted by permission of DAW Books.

She Who Knows: Firespitter by Nnedi Okorafor will publish August 20; you can pre-order here and on Amazon.

Need more entertainment? Pedestrian Television has launched on 9Now where you can watch iconic TV series like Just Shoot Me, cult classic movies like Fright Night, and homegrown content like Eternal Family. Watch all that and more for free, 24/7 on 9Now.