Like the AK-47, the Soviet RPG-7 rocket propelled grenade has become one of the most widely-distributed infantry weapons on Earth, used by everyone from E8 nations to guerrilla insurgency groups in every major conflict since Vietnam. But their ubiquitousness nature has kicked off a global race focused on how to beat them.

First developed by the Soviet Union shortly after WWII, the original RPG-2 was Russia’s answer to the American bazooka and German Panzerfaust. Its successor, the RPG-7, retains much of the same functionality — a handheld, unguided, rocket-propelled grenade launcher designed to kill or disable armoured units (tanks, APCs, etc) and fortified positions. For a weapon measuring just over a yard long with a 40mm bore and weighing about 7kg, the RPG-7 packs one hell of a wallop.

Its rounds measure 40mm – 105mm in diameter and weigh 2kg to 5kg, depending on the type of charge — HEAT for anti-armour, fragmentation for anti-personnel, or a tandem charge for defeating reactive armour. Using a gunpowder propellent, the round travels up to 295m/s and is accurate to up to 500 m (max range 920 m) thanks to a set of air-deployed stabilising fins.

Tandem charges — in which a weaker initial charge explodes first to create a channel for the secondary HEAT explosive to penetrate the target’s reactive armour — have proven exceptionally effective against armoured units. They can burn through up to 500 mm of steel armour. And it’s these rounds that have set off an arms race between opposing armour and RPG technologies.

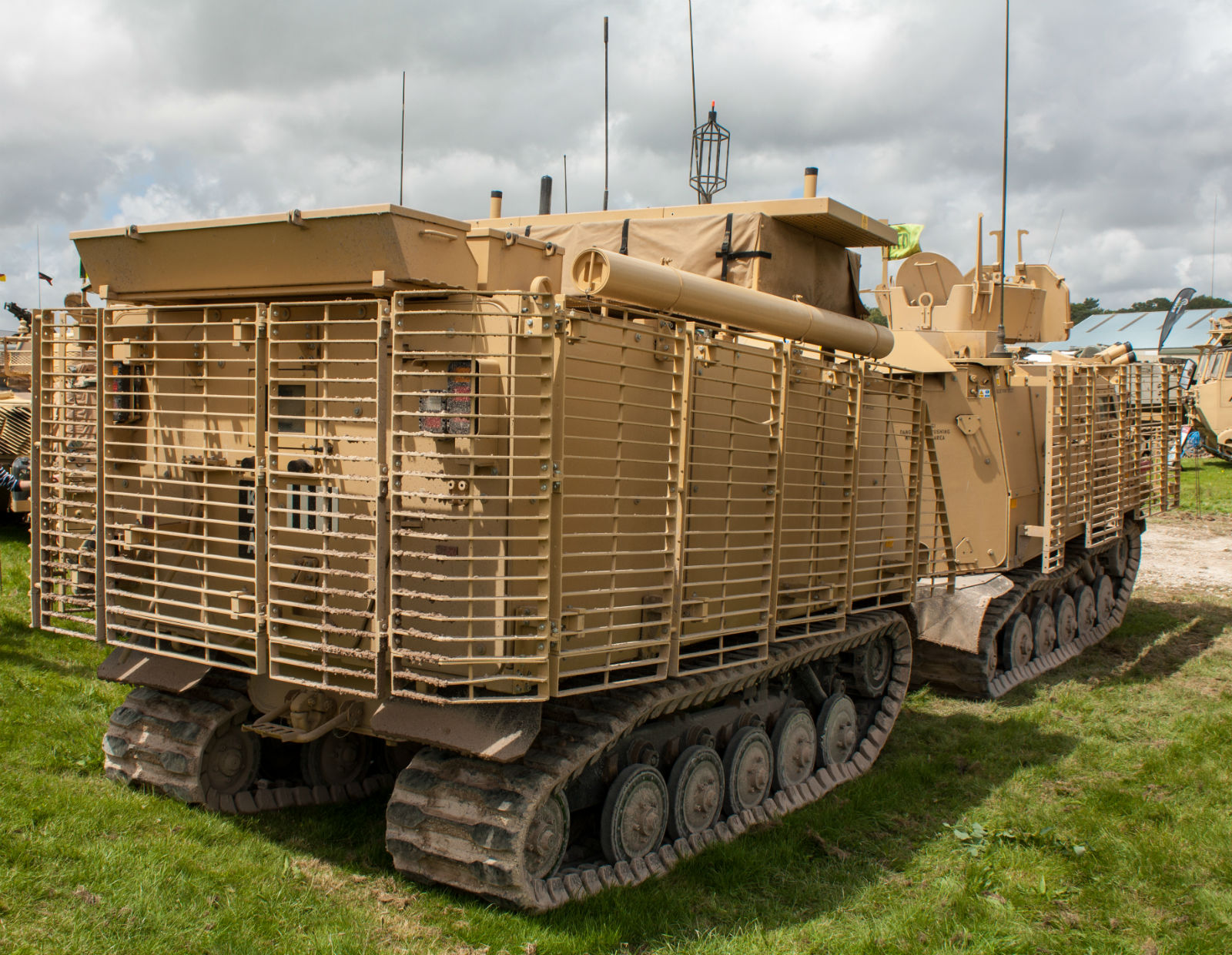

Picture: Simon Q

The first defensive advancement debuted at the tail end of WWII, when armoured units began sporting wire mesh skirt armour (aka cage, slat, bar, or standoff armour). This densely-slatted secondary protection sits in front of the tank’s primary skin, trapping the RPG round between a pair of bars far enough away that the initial shaped charge cannot damage the armour, while short circuiting the piezoelectric precursor to either prevent the HEAT charge from detonating or at least denying the charge’s molten jet a route into the tank’s interior.

Essentially, since the tandem charge is only effective if it actually hits the target, cage armour is designed to catch the incoming RPG round before it does. Originally, this rigid slatted metal grid fitted around key sections of the vehicle was made from heavy steel or aluminium, weighing about 20-30 kg/sqm. However modern day composite variants, such as Chobham armour — or BAE’s LROD system employed by the Buffalo MPV — offer superior protection compared to steel cages yet weigh less than aluminium.

That said, slat armour is far from foolproof. Instead it offers what’s known as statistical protection; that is, while the system doesn’t offer a complete defence against RPGs, it does lower the probability that a tandem-charge shot will be successful by 50 to 70 per cent, depending on where and how the RPG connects. If a second shot happens to strike the same spot, you’re in trouble.

But even with cage armour’s shortcomings, the weight savings and improved defensive capabilities that it provides far outweigh its potential failure risks. As such, cage armour is extensively employed in armoured divisions the world over, from the IDF’s Caterpillar D9R armoured bulldozer to the General Dynamics Stryker and M113 APC to Russian T-62 and American M1 Abrams tanks.

But RPG manufacturers haven’t waived the white flag just yet. “RPG manufacturers are applying protective layers at the base of the cone, thus avoiding potential short-circuits caused by deformation”, an unnamed armour expert told Defence-Update. “In fact, as it will hit at an angle, the behind armour effect could be increased, as the spall is distributed at a larger lethal cone, hitting more of the vehicle occupants.”

Armour designers, however, are already hard at work building lighter, sturdier, and more secure defensive systems to counter this increased RPG threat. The game of oneupmanship between RPG and armour designers doesn’t look to be ending anytime soon. [Defence Update – Wiki 1, 2, 3]