Scientists have identified nearly 100 previously unknown volcanoes in West Antarctica, which, in addition to the 47 already known to exist in the region, makes it one of the largest concentration of volcanoes in the world.

Unlike Antarctic volcano Mount Erebus (pictured), all of the newly identified volcanoes lie hidden beneath the continental ice sheet. (Image: NASA/Jim Yungel)

New research released in a special Geological Society publication series identifies 91 new volcanoes in a region known as the West Antarctic Rift System, a 3,541km-long (3,500 km) area that extends from Antarctica’s Ross Ice Shelf to the Antarctic Peninsula. All of these volcanoes are buried beneath the Antarctic ice sheet, some as deep as two miles. They range in size from 325 to 12,600 feet (100-3,850 meters), the largest being as tall as the Eiger in Switzerland.

The scientists who conducted the study, Max Van Wyk de Vries and Robert Bingham from the School of GeoSciences at the University of Edinburgh, say this concentration is bigger than East Africa’s volcanic ridge, which would make it the densest concentration of volcanoes in the world — though some geologists say this claim is grossly overstated (more on this in just a bit). It’s not known how many, if any, of the newly-discovered volcanoes are active, but scientists are voicing concerns that an eruption could exacerbate the effects of climate change on the frozen continent.

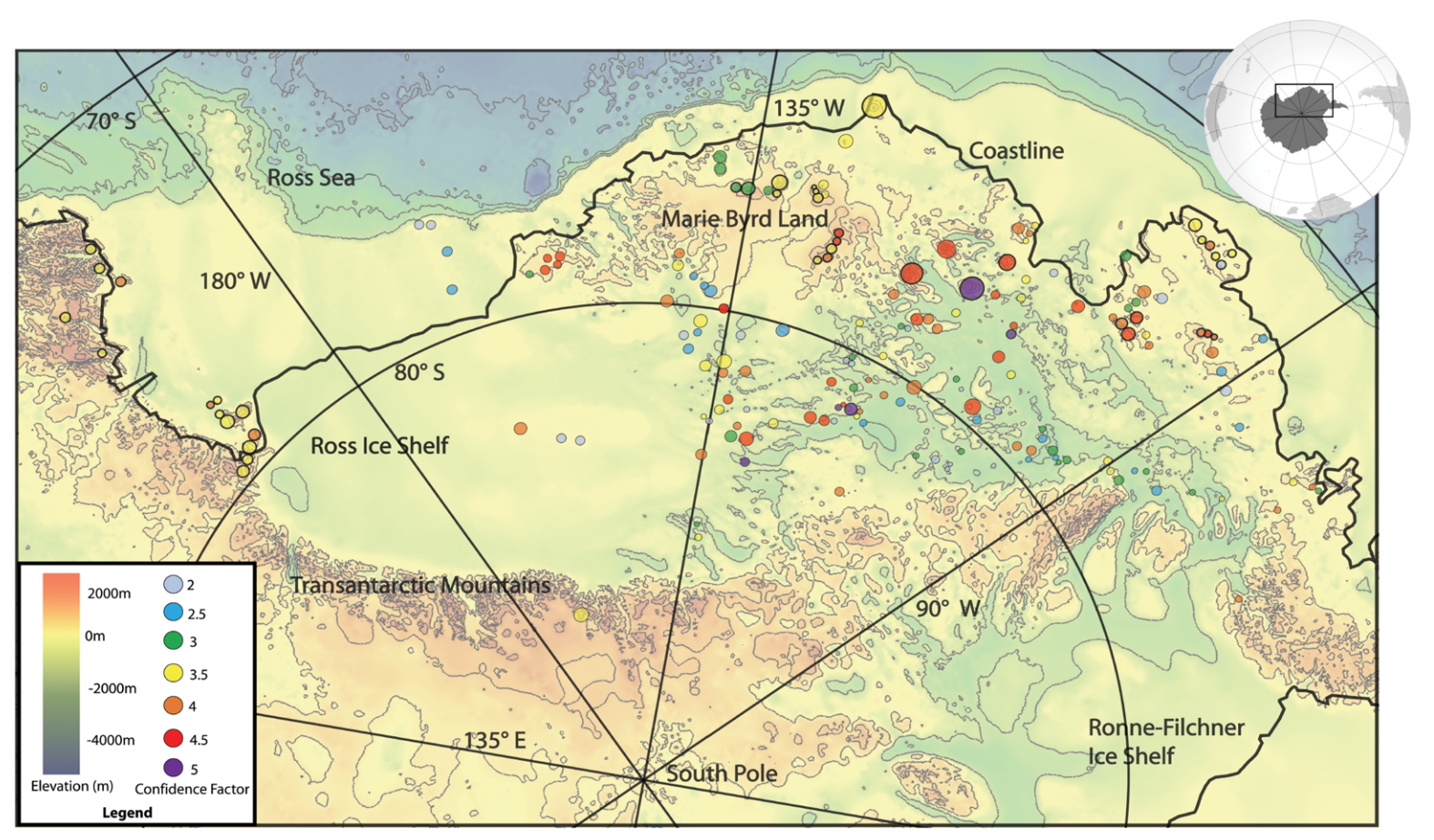

Location map of obscured cone-like structures across the West Antarctic Rift System. Circle colour represents confidence factor, circle size represents diameter, and circles with black rims represent prior discoveries. (Image: M. V. W. de Vries et al., 2017)

Max Van Wyk de Vries, a third-year undergrad, got the ball rolling on this discovery after noticing possible traces of volcanism on publicly-available radar maps of Antarctica. He suggested to the school’s geologists that a more rigorous survey be conducted to confirm his initial findings, and they agreed. With the help of Bingham, de Vries remotely surveyed the underside of the ice sheet for hidden peaks of basalt rock, similar to those found atop other volcanoes, and where the tips push just slightly above the ice. The shape of the land underneath the thick layers of ice were analysed using measurements from ice-penetrating radar; the researchers were on the hunt for cone-like structures extending into the ice sheet. These findings were compared with satellite and database records, along with geological information from aerial surveys.

“Antarctica remains among the least studied areas of the globe, and as a young scientist I was excited to learn about something new and not well understood,” said de Vries in a statement. “After examining existing data on West Antarctica, I began discovering traces of volcanism. Naturally I looked into it further, which led to this discovery of almost 100 volcanoes under the ice sheet.”

Indeed, the discovery of so many previously-unknown volcanoes changes our conception of Antarctica as a volcanic region, both in the past, present, and future. Further research will help geologists better understand how volcanoes might influence changes in ice sheets over long timespans, while also improving our understanding of the continent’s climatic past.

Unfortunately, the new results don’t indicate which of these volcanoes might be active, or have the potential to erupt, but this new study should inspire further research and seismic monitoring in the area. The researchers say it’s imperative that we figure this out as quickly as possible. Should one or more of these volcanoes erupt, it could further destabilize West Antarctica’s ice sheets (which are already being affected by human-instigated global warming) and speed up the flow of meltwater into the ocean. Back in 2013, researchers from Washington University detected at least one active, ice-covered volcano in Antarctica (also only the West Antarctic Ice Sheet), so it’s reasonable to assume others may be active as well.

Scientists aren’t entirely sure what happens when under-ice volcanoes erupt, but these events could cause underground magma and fluids to force open new paths and fracture rock, according to the Washington University researchers. A serious eruption could melt the bottom of the ice sheet immediately above the volcano’s vent, but we really have no idea what would happen after that.

“This is a major step forward in understanding solid Earth processes beneath the Antarctic ice sheet,” said Mike Coffin, a researcher at the University of Tasmania’s Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS), in an interview with Gizmodo. “Combining different data types — magnetic, gravity, and satellite imagery — with a digital elevation model and existing volcano databases has proven extremely fruitful, and the work will sow the seeds for much future research on Antarctica.”

Coffin, who wasn’t involved with the new study, says the researchers’ approach is admirable, and the results fascinating — but he’s taking issue with a central claim made by the authors.

“I’m not particularly enamoured with the hyperbole — ‘one of the world’s largest volcanic provinces’,” he said. “Clearly the global mid-ocean ridge system (and the resulting ~50% of the Earth’s surface that is ‘pure’ oceanic crust) is the world’s largest volcanic province, and even segments of the mid-ocean ridge system (e.g., the Mid-Atlantic Ridge) are much larger than this West Antarctic volcanic province. However we shouldn’t inhibit youthful exuberance!”

Coffin says he wouldn’t be surprised if some of these newly discovered volcanoes are active, and he’d like to see a similar study done of the entire Antarctic continent. Mount Gaussberg, for example, is a young volcano protruding above the ice in East Antarctica, and Coffin says there may be many more under East Antarctic ice, as well.

Red-hot magma bursting through the Antarctic ice sheet evokes a particularly powerful mental image. Perhaps one of these newly discovered volcanoes will blow within our lifetimes, and we’ll actually get a chance to see it. It would be a song of fire and ice, indeed.