Recent years have brought record-breaking wildfires, hurricanes, and other natural disasters supercharged by climate change. But even to our jaded modern eyes, the weather that befell Bristol in Western England at the turn of 17th century is pretty shocking.

The meteorological situation in Bristol occurred during a short timespan within the Little Ice Age called the Grindelwald Fluctuation, so named for the expansion of a Swiss glacier by the same name. A team of researchers from the University of Bristol and University College London recently inspected Tudor-era chronicles describing the weather phenomena, which included huge floods, snowstorms, frigid temperatures, and storms. Their findings are published in the Royal Meteorological Society journal Weather.

“This was taking it down on the level of one city, one place, but there’s no reason to think it would be atypical,” said Evan Jones, a historian at the University of Bristol and lead author of the recent paper, in a video call.

Kicking off in 1560, the 80-year Grindelwald Fluctuation is typically blamed on a slew of volcanic eruptions across the Atlantic, which temporarily lowered temperatures around the world as particles from the eruptions clogged the atmosphere and blocked sunlight. The cascading effects of this led to famine and mass starvation in the 1590s, and unusual weather continued for decades.

“Although explosive volcanic eruptions cause cooling globally (that lasts for several years), regionally weather can become more chaotic, especially as the thing that causes the change is so abrupt,” said co-author Anson Mackay, a geographer and paleoecologist at University College London, in an email. “Cold snaps, floods, droughts are all possible, but it is their extreme nature that characterises them all.”

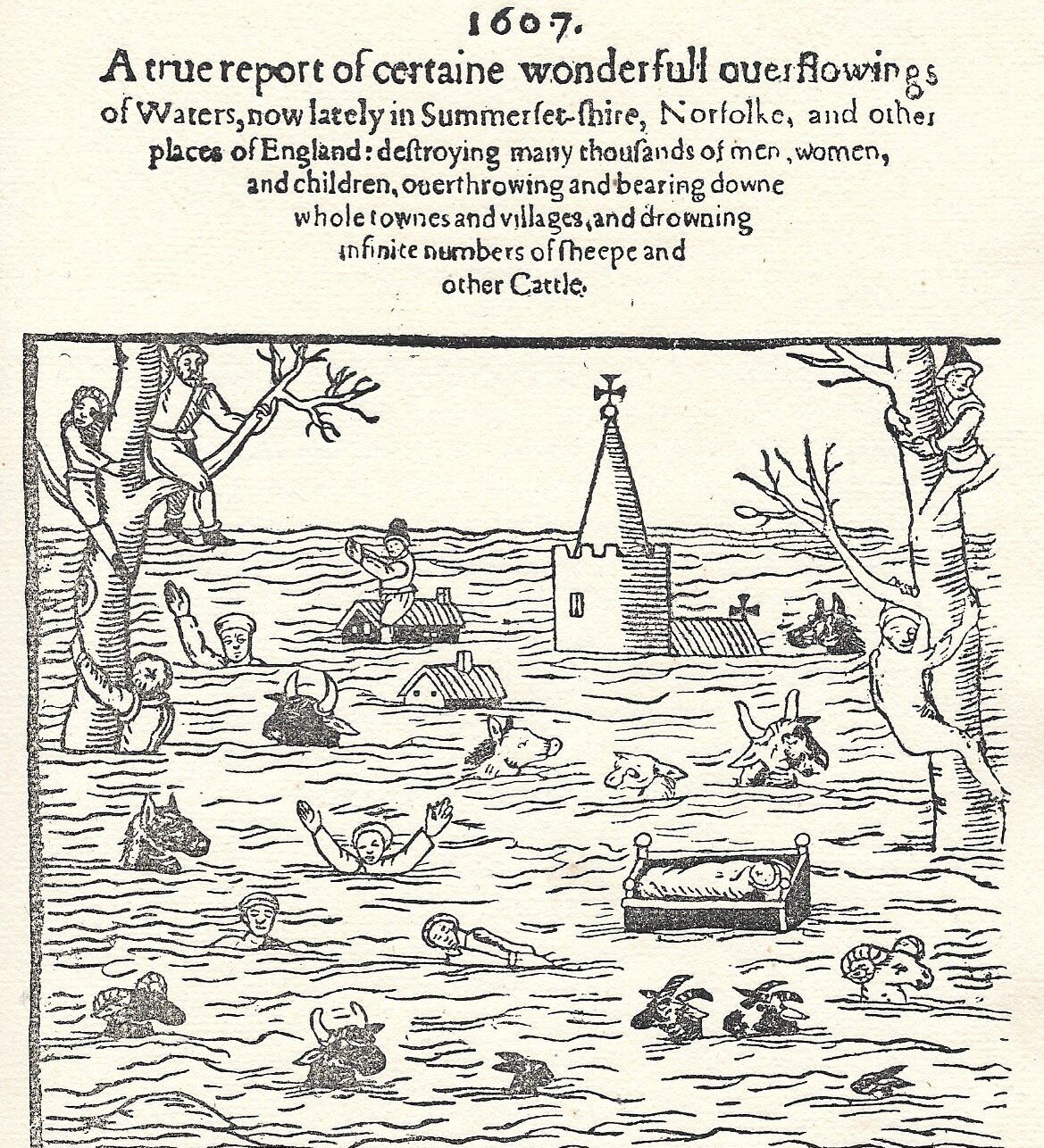

In Bristol, the sustained climatic condition meant blizzards in October and floods that left water lines that persist to this day on some churches in town. Contemporary chroniclers in the area by and large had accurate reports, Jones said, though they were at times “providential” and “messianic” in their language. The October snow, for example, was “greatest snow that ever was known by the memory of man, which continued four days,” and the winter of 1610-11 was “very stormy in so much that it occasioned the greatest shipwrecks that ever was known in England,” according to contemporary accounts.

Given the frequency and severity of the events over the years, you can’t blame the chroniclers for having such grim vocabulary. Seasonally, they would go through “sweating sulphurs drying up the moistures of the earth, to cause barrenness with scarcity,” one documented, “then freezing and cold winters in more than usual extremity to annoy us; another time by floods and overflowings of waters breaking from the bounds of the Seas, in which merciless element many hundreds have perished and have lost both life and goods.”

Some of the events were corroborated by news pamphlets elsewhere in the country, like in London, where a frost in the winter of 1607-8 led to the Thames freezing over, and city residents, trying to keep their spirits up, held a “Frost Fair” out on the ice.

“People will say Shakespeare writes for all time, but he was writing for an audience at the time,” Jones said. “When Shakespeare put on The Tempest for people, it would have resonated with them.”

Studying past weather can lead to plenty of insights into life at the time, as well as how historical events might have gone differently had the wind blown a different way, so to speak. Last year, for example, researchers concluded that a “climate anomaly” made both World War I and the 1918 flu pandemic a lot more deadly than they might have been otherwise.