At its heart, Mario Paint wasn’t really a video game. There was no defined end point players raced towards, no one to stomp on, and definitely no helpless princess in peril. Like educational software, it was designed to help improve real word skills as it was played. Not in the maths, sciences, or other academic pursuits, but in the arts. Nintendo cleverly made Mario Paint look like a game, with the company’s popular characters sprinkled throughout, but it was first and foremost a creative tool that introduced many kids to computer graphics and the pixel-pushing digital tools of the time. In a time when parents were worried about how much time kids were devoting to video games, Mario Paint helped repaint the SNES (pun intended) as more than just a so-called mindless gaming system.

It only ever existed on one system: the Super Nintendo, and that’s a shame, because Mario Paint was a masterpiece that made the console so much more than just a video game system for me.

Released two years after the Super Nintendo debuted in Japan, Mario Paint was also one of the rare SNES titles that came with a custom hardware accessory. Not a blaster or a unique gamepad, but a computer mouse and pad. I’d be lying if I said that wasn’t partly what attracted me to Mario Paint. Mouse-driven computer interfaces had been around for quite a while before Mario Paint debuted, but I didn’t own a Windows PC until 1996, making the accessory the first mouse I ever owned. It looked and worked just like the ones beige desktop computers used, and it helped Mario Paint feel like a legitimate creative tool. Had kids been forced to express their creativity through the limited controls of a gamepad, Mario Paint just wouldn’t have hit the same.

For those not familiar with Mario Paint, it offered several ways for kids to creatively express themselves, either through free-hand drawing, the creation of pixel sprites by painstakingly colouring in grids, simple colouring book activities, basic animations, and even a music sequencer chock full of classic Nintendo sound effects that could be piece together to create songs. It was a surprisingly robust creativity tool for an SNES game, but at first the novelty quick wore off with my siblings and I. Mario Paint was chock full of tools, but to kids who didn’t understand the creative potential, a simple fly-swatting game, designed to familiarise kids with how the mouse accessory worked, was the most compelling reason to pop in the cartridge.

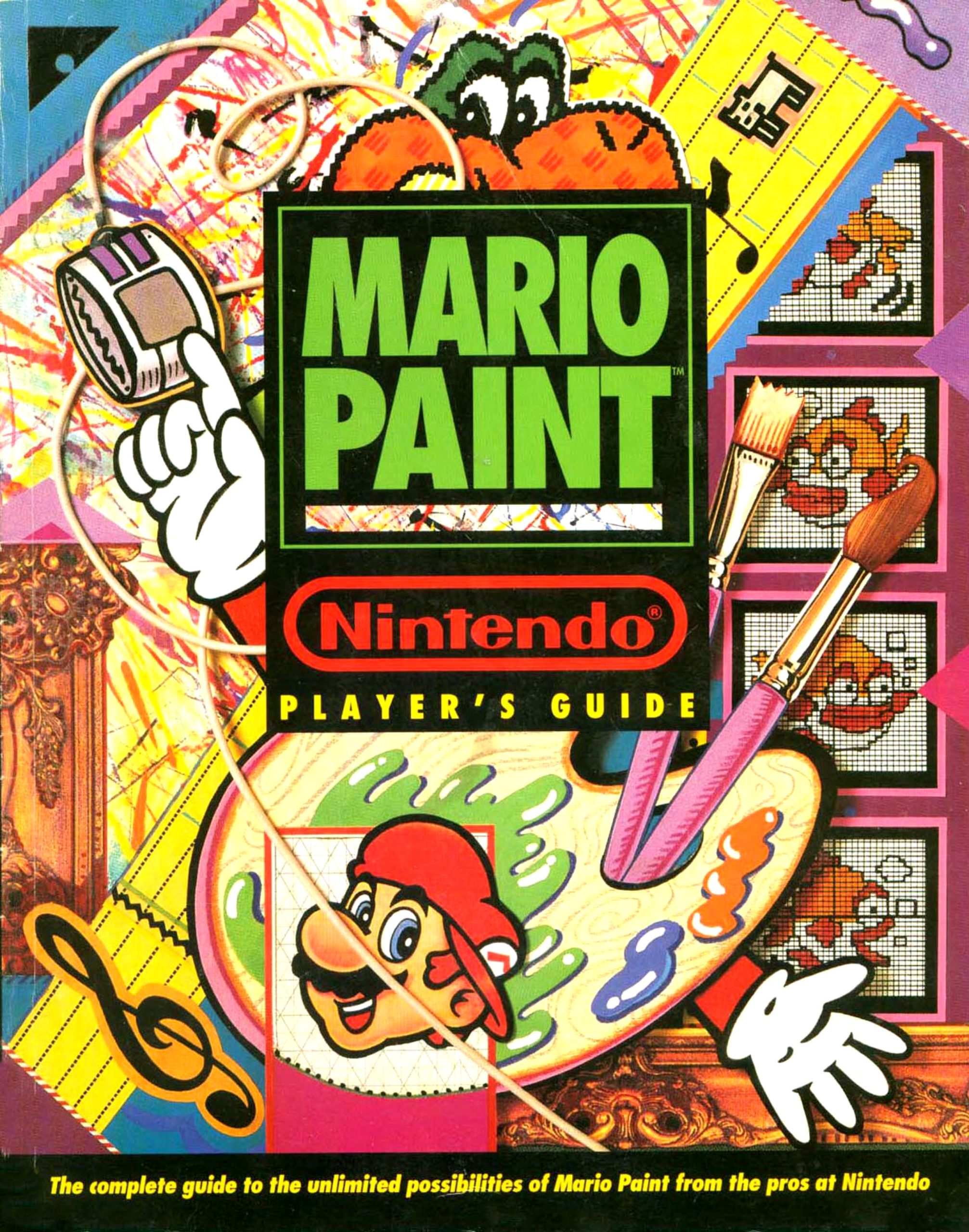

That all changed one afternoon when at a video game store my siblings and I found the official Mario Paint Nintendo Player’s Guide. (You can actually find a scan of the entire book here.) Thumbing through the pages we discovered a wealth of tutorials that completely blew our teenage minds. Could you really do all of this in Mario Paint?

The book revealed how to create the same kinds of simple sprite animations used in the SNES games we played, how the various tools could be combined to create surprisingly elaborate animated scenes, and other ways to use the Mario Paint tools we would have never figured out on our own. What completely sold us on the book (to this day it’s the only video game guide book we’ve ever purchased) was a section on composing music using the Mario Paint sequencer, including examples of how to recreate the Super Mario music, and even the Star Wars theme.

My parents still have our copy of that book, which today looks like it’s been through several world wars. But it’s a testament to how much time we spent pouring through its pages, learning to master the tools we previously didn’t realise we had. Copying the musical compositions from the screenshots in the guide was a huge pain and incredibly time-consuming, but the payoff of hearing Mario Paint play back a recognisable tune was always completely worth it, and it inspired us to spend even more time trying to recreate our favourite songs. To this day, there are still people composing masterpieces in emulated versions of Mario Paint’s song composer, if you’re looking for a nostalgic YouTube rabbit hole to fall down.

With my new skills, Mario Paint eventually became more than just a fun way to create digital doodles. As an aspiring pixel-pusher who dabbled in home videos, prosumer-calibre editing and animation tools like a Video Toaster (released the same year the SNES was) were far outside my production budget which was usually zero dollars. One day I realised the Super Nintendo could be connected to our VCR just as easily as it was connected to our TV, and suddenly our family’s video game system became a tool I could use to create simple title sequences and animations that I could splice into my crude video productions.

When the touchscreen Nintendo DS arrived years later, I always hoped that Nintendo would revive the game on the tiny system (other animation tools for the DS eventually filled the void) and I would still happily shell out a small fortune to be able to play the original Mario Paint on the Switch with full support for the console’s touchscreen — but that’s probably wishful thinking. Despite being one of the best selling titles for the Super Nintendo — with an impressive 2.3 million copies sold — Mario Paint was born and died on the SNES. In 1999, what has been described as the spiritual successor to Mario Paint was released in Japan called Mario Artist featuring a more modern looking mouse and real 3D graphics. However, it was only playable on the obscure N64 64DD accessory: a floppy disk drive peripheral that was such a flop it was never released in North America.

Mario Paint was Nintendo doing what Nintendo does best. It was about as outside the box as a console video game could be, and it paired an easy to use kid-friendly interface with surprisingly deep and capable creative toolset. Had the modern internet been around in 1992, I can only imagine the wealth of Mario Paint YouTube tutorials I would have had access to as a teen, and what kind of artistic creations I would have been able to produce.