On July 12, it’ll be 199 days since the Webb Space Telescope launched from French Guiana. Momentously, it’ll be the first day that the public actually sees full-colour images taken by the advanced telescope.

The image release will begin at 10:30 a.m. ET on Tuesday, and the pictures will be published on NASA’s website. NASA officials remain tight-lipped about the number of images that will be shared, but astronomers told Gizmodo that we’re about to see distant worlds and ancient galaxies in astonishing detail.

On Friday, NASA announced the telescope’s first five cosmic targets: the Carina Nebula, the exoplanet WASP-96b, the Southern Ring Nebula, a deep field image of SMACS 0723, and Stephan’s Quintet, a group of five galaxies 270 million light-years away.

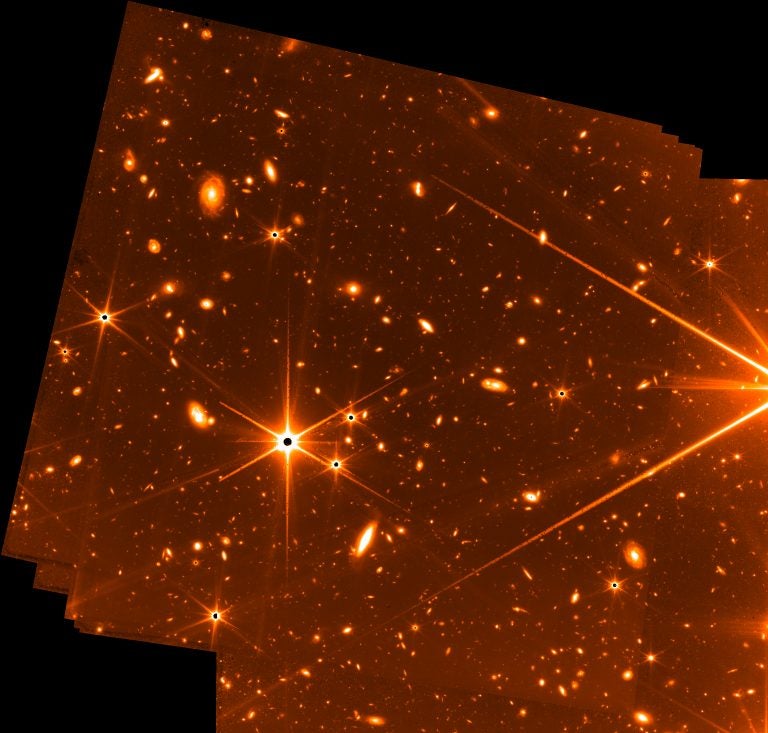

So far, the only images we’ve seen from Webb are the star-spangled shots the telescope took when aligning its mirrors and the dazzling first look at the Large Magellanic Cloud, which was taken to test the telescope’s MIRI instrument. Neither of those images were in full colour; Webb collects light in the infrared and near-infrared wavelengths, so scientists will need to laboriously translate the images’ contents into a rainbow of visible light.

Tuesday’s big reveal will be transformational in both what we’ve seen from Webb so far and what we’ve seen from any telescope before it. Four of the cosmic targets have been imaged before by Hubble, but Webb is much more powerful.

“We knew how amazing this telescope was meant to be, and even then it blew away all my expectations,” said Dan Coe, an instrument scientist for Webb’s NIRCam instrument and an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute, in a phone call with Gizmodo. “On July 12, the universe will never be the same.”

It’s been a long time coming. The telescope that would eventually become Webb was first proposed in 1989, before the Hubble Space Telescope even launched.

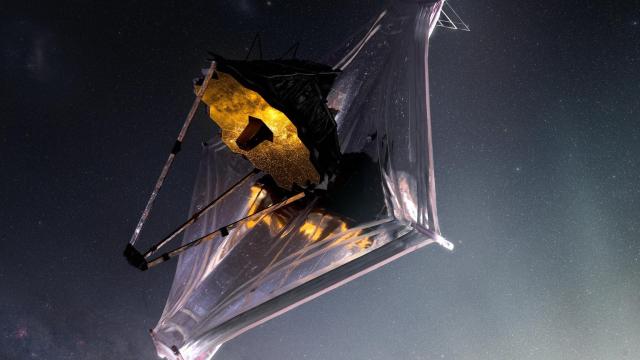

Now in its final form, Webb looks like a cosmic sailboat; its 21.34 m-long, multilayered sunshield makes up the vessel’s hull, and its 6.40 m primary mirrors its sail. But Webb isn’t sailing anywhere — rather, it sits at a point in space 1 million miles from Earth called L2. L2 is the second Lagrange Point, what NASA describes as a “wonderful accident of gravity and orbital dynamics” that will allow Webb to stay stable in space with minimal course corrections.

Webb’s placement at L2, combined with the telescope’s extremely precise launch, means it will likely be in use for the next 20 years — a happy accident, considering the minimum baseline for the telescope’s operation was just five years.

Webb’s sunshield will keep it cold, allowing it to pick up infrared light emanating from some of the faint and distant in the universe. You can check the temperatures of the telescope and its instruments in real time here.

Webb is not replacing Hubble, which has been imaging the sky for over 30 years in spite of occasional shutdowns and even repair missions in space. What we’ve seen from Webb so far has indicated a much smoother process than Hubble’s faltering first days. But the two telescopes have little overlap in how they look at the universe; Hubble sees mostly in optical and ultraviolet wavelengths, and Webb exclusively in infrared and near-infrared.

“Hubble can do a little observation in the very near infrared, but once you go beyond that, Webb is 100 and in some cases as much as 1,000 times more sensitive than what we’ve had before, and 10 times sharper,” said Klaus Pontopiddan, a Webb project scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, in a phone call.

“Pretty much every image that Webb takes is going to be better than the Hubble Ultra Deep Field,” Coe said, referring to a famous image of the cosmos that contains nearly 10,000 galaxies spanning billions of light-years. “In some cases, the Ultra Deep Field still might be better at some wavelengths — but then Webb goes out to much farther wavelengths, and it also has much better resolution. It’s just hard not to surpass what’s been done by a lot.”

In a press conference last week, NASA officials revealed that the July 12 images would include the deepest-ever image of our universe and at least one exoplanet. The agency’s statement today has revealed the deep field image to be of SMACS 0723, a cluster of galaxies that distort the more ancient light beyond them, making it easier to see distant, faint objects. It also revealed the exoplanet will be WASP-96b, a gas giant 1,150 light-years from Earth.

Webb has four science goals, which give us an inkling of what we might see beyond next week. Webb is charged with collecting some of the earliest light in the universe, observing the formation of some of the first galaxies, peering through clouds of dust to see the birth of stars and protoplanetary systems, and scrutinizing the atmospheres of exoplanets and some objects within our Solar System.

“We’ve looked 97% of the way back to the Big Bang, but there’s that the first 3% of cosmic time, the first 400 million years that we’ve yet to see a single object, what it looked like,” Coe said. “We knew how amazing this telescope was meant to be, and even then it blew away all my expectations.”

The upcoming images involved all four of Webb’s scientific instruments: the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), which imaged the Large Magellanic Cloud, the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam), the Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec), and the Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph/Fine Guidance Sensor (NIRISS/FGS.)

On Wednesday, NASA teased another image from Webb, taken with the FGS instrument, which was developed by the Canadian Space Agency. The image is a composite of 72 exposures taken over 32 hours, and is one of the deepest images of the universe ever taken (until this coming Tuesday, it seems). We’re going to have to get used to records being broken and rebroken as Webb hits its stride.

Tuesday’s images will be a portent of the science to come from the telescope, whose observational docket has already been filled for the next year. NASA officials noted in a press conference last week that one of Webb’s first targets (part of its Early Release Science programs) will be Jupiter and some of its moons. The early release programs will take up Webb’s first five months of observation and can be looked at here.

Besides being beautiful, the upcoming release will also hopefully be a relief to you, reader, as the same five illustrations we keep using of the telescope can be replaced with actual star-studded imagery.

Come Tuesday, we will know more about the history of the universe that we do today. Even to the untrained eye, it’ll be a feast.

More: NASA Releases Ridiculously Sharp Webb Space Telescope Images