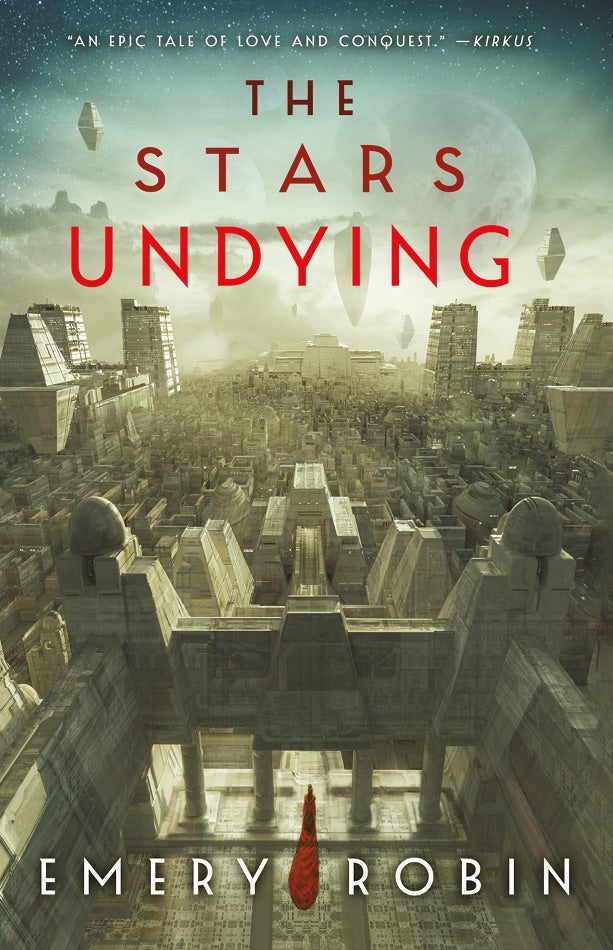

The Stars Undying, the upcoming sci-fi debut from Emery Robin, introduces an interstellar princess forced into circumstances that’ll require every bit of royal strength she can muster to overcome. It’ll be released in November, but Gizmodo is thrilled to share a generous excerpt from the book today.

Here’s a description of the book, followed by its first two chapters.

Princess Altagracia has lost everything. After a bloody civil war, her twin sister has claimed both the crown of their planet, Szayet, and the Pearl of its prophecy: a computer that contains the immortal soul of Szayet’s god.

So when the interstellar Empire of Ceiao turns its conquering eye toward Szayet, Gracia sees an opportunity. To regain her planet, Gracia places herself in the hands of the empire and its dangerous commander, Matheus Ceirran.

But winning over Matheus, to say nothing of his mercurial and compelling captain Anita, is no easy feat. And in trying to secure her planet’s sovereignty and future, Gracia will find herself torn between Matheus’s ambitions, Anita’s unpredictable desires, and the demands of the Pearl that whispers in her ear.

For Szayet’s sake and her own, she will need to become more than a princess with a silver tongue. She will have to become a queen as history has never seen before.

Chapter One — Gracia

In the first year of the Thirty-Third Dynasty, when He came to the planet where I was born and made of it a wasteland for glory’s sake, my ten-times-great grandfather’s king and lover Alekso Undying built on the ruins of the gods who had lived before Him Alectelo, the City of Endless Pearl, the Bride of Szayet, the Star of the Swordbelt Arm, the Ever-Living God’s Empty Grave.

He caught fever and filled that grave, ten months later. You can’t believe in names.

Three hundred years is a long time to call anything Endless, for one thing. Alectelo is no different, and the pearl of the harbour-gate was cracked and flaking when I ran my hand up it, and its shine had long since worn away. It had only ever been inlay, anyway. Beneath it was brass, solid and warm, and browning like bread at the edges where the air was creeping through.

“It needs repairs,” said Zorione, just behind my shoulder.

I curled my fingers against the metal. “It needs money,” I said.

“She won’t give it,” Zorione said. She was sitting on a nearby crate already, stretching her legs out in front of her. She had complained of her old bones and aching feet through every back alley and tunnel in the city, and been silent only when we passed under markets, where the noise might have carried to the street. “Why would she?” she went on, without looking at me. “She never comes to the harbour. Are the captains and generals kept in wine and honey-cakes? Yes? That keeps her happy.”

I said nothing. After a moment she said, “Of course — it’s not hers,” and subsided.

I had not meant her to mistake my silence for offence, but I knew I ought to be grateful for her devotion. Nevertheless it was not a question of possession that stirred me, looking at the curling rust on that gate framing the white inlet where our island broke to the endless sea. Nor was it a question of reverence, though it might have been, in better times. It was the deepest anger I had ever felt, and one of the few angers I had never found myself able to put aside. It was the second time in my life the queen of my planet had been careless with something beautiful.

“It wouldn’t matter, anyway,” I said, and let my hand fall. “This is quicksilver pearl. It only grows in Ceiao these days.”

It was a cool day at the edge of the only world I had ever known. The trade winds were coming up from the ocean, smelling of brine and exhaust, and the half-moon-studded sky was a clear and cloudless blue. At the edge of my hearing was the distant hum of rockets from across the water, a low roar like the sound of the lions my people had once worshiped. I took it as an omen, and hoped it a good one. Alectelans had made no sacrifices to mindless beasts, these last three centuries. If Alekso heard my prayers, though, it was months since He had answered them, and I needed all the succor I could get.

“How long until the ship?” I said.

I had asked three times in the last half-hour, but she said patiently, “Ten minutes,” as if it were the first time. “If she hasn’t caught it yet,” and she made a sign against bad luck in the air, and spit over her shoulder. It made me smile, though I tried not to let him see it. She was a true Alectelan, Sintian in name and in parentage but in heart half orthodoxy and half heathenism, in that peculiar fanatical blend that every born resident of the city held close. And though she carried all unhappiness as unfailingly as she carried my remaining possessions, I had no interest in offending her. She had shown no sign, as yet, of being capable of disloyalty. Still: I had so little left to lose.

The water was white-green and choppy with the wind, and so when our ship came skipping across the sea at last only the sparks gave it away, meandering orange and red towards the concrete shore like moths. It slowed at the very last moment, and skidded onto the runway in a cloud of exhaust, coming to a stop just yards from our feet.

My maid was coughing. I held still, and listened for the creak of a hatch. When the smuggler appeared through the drifting grey particulates a moment later, shaven-headed and crooked-toothed and grinning, Zorione jumped.

“Good morning,” I said. “Anastazia Szaradya? We spoke earlier. I’m — ”

“I know who you are,” she said in Szayeti-accented Sintian. Her eyes took me in — cotton dress, dust-grey sandals, bare face, bare arms — before they flicked to Zorione, behind me. “This is the backer, yes?”

I kept my smile wide and pleasant. “One of them,” I said. “The rest are expecting our report from the satellite in — I’m sorry, was it three hours? Four?”

“By nightfall, madam,” Zorione said, looking deeply uncomfortable.

I gave her an apologetic look behind the smuggler’s back. If I had had choice in who to play the role of the backer, I would not have chosen Zorione, who as long as I had known her had despised deception almost as fiercely as rule-breaking, and rule-breaking like blasphemy. But she knew as well as I did what a luxury choice had become. “By nightfall,” I repeated. “Shall we board the ship?”

The smuggler narrowed her eyes at me. “And how long after will the pearls be sent to the satellite?” she said. “You said three days?”

I flicked my eyes to Zorione, who cleared her throat. “A week,” she said. “The transport ship will bring them, if they find her safe and sound. Only if,” she added, in a burst of improvisation. I gave her a quick encouraging nod.

“A week?” said the smuggler. “For a piece of walking bad luck? Better I should be holding a bomb! Was this what we agreed to?”

Zorione’s face went blank. “You know,” I said hastily, “you’re very right — speed is of the essence. I would personally prefer to leave the system as soon as possible. Madam Buquista, might your consortium abandon the precautionary measures we discussed? I understand the concern that the army not trace the payment back to Madam Szaradaya — of course the Ceians might, too, and come to investigate her — but is that really my highest priority? Perhaps instead — ”

The smuggler snorted. “Hush,” she said. “Fine. Keep your precautions. You, girl, can keep your patience. Meanwhile,” she nodded at Zorione’s outraged face, “when your ship comes for her, we will discuss what delay fees I collect, hmm?”

Zorione looked admirably more unhappy at this, and I would have nodded at her to put up a lengthy and losing argument, when there was a low, dull hum, akin to the noise of an insect.

The sky wiped dark from horizon to horizon. The sea, which had been glittering with daylight, went black at once; the shadow of the smuggler’s ship swelled, swept over us, leaving in darkness. The smuggler swore — I whispered a prayer, and I could see Zorione’s silhouetted hands moving in a charm against ill fortune — and above us, just where the sun had been and twenty times its size, the face of the Queen of Szayet opened up like an eye.

She was smiling down at us. She was a lovely woman, the queen, and though holos had a peculiar quality that always seemed to make it impossible to meet anyone’s eyes, her gaze felt heavy and prickling as it swept over the concrete and the sea and the pearl of the harbour-gate below. She had braided her hair in the high Ceian style, and she had thrown on a military coat and hat that I was almost certain had belonged to the king who was dead, and she had painted her mouth, hastily enough that it smeared at the corner, and dripped there as if she had just bitten into a raw piece of meat. Around her left ear, stretching up to her hairline, curled a dozen golden wires, pressed so closely to her skin they might have been a tattoo. An artfully draped braid hid where I knew they slipped through her temple, into her skull. In her earlobe, at the base of the wires, sat a shining silver pearl.

She said, sweetly and very slowly — I could hear it echo, as I knew it was doing on docks and in cathedrals, in marketplaces and alleyways, across the whole city of Alectelo, and though I had seen the machines in the markets that threw these images into sky, though I had had laid hands on them and shown them my own face, my breath caught, my heart hammered, I wanted to fall to my knees — — “Do you think the Oracle blind?”

She paused as if for a response. There was none, of course. She added, even more sweetly, “Or perhaps you think her stupid?”

“Time to go,” said the smuggler.

We scrabbled ourselves up the ladder into the hole at the top of the ship as best we could: the smuggler first, then me, Zorione taking the rear with the handles of my bags clenched in her bony fingers. Above me, the queen’s voice was rising: “Did you think I would not see,” she said, “did you think the tongue and eyes of Alekso Undying would not know? I have heard — I will be told — where the liar Altagracia Caviro is hiding. I will be told in what harbour she dares to stand, I will be told in what ship she dares to fly. You are bound to do her harm, all you who worship the Undying — you are bound to do her harm, Alekso wishes it so — ”

Zorione, swaying on the rungs, made another elaborate sign in the air, this time against blasphemy. “Please don’t fall,” I called down to her. “I can’t afford to lose you. But I appreciate the piety.” She huffed, and seized hold of the ladder again.

When we had all tumbled into the cramped confines of the ship, the smuggler slammed the hatch shut above my head, and shoved lumps of bread and a pinch of salt into our waiting hands. The bread was hard as stone, and tasted like lint — it must have come out of her pocket, a thought I immediately decided not to contemplate — but I swallowed it as best I could, and smeared the salt onto my tongue with my thumb. The queen’s voice was echoing even through the walls, muffled and metallic. I heard worship a lying and demand by right and levy upon you, and turned my head away.

The smuggler had gone ahead of me, through the bowels of the ship. I made to push past Zorione, but she caught my arm at the last moment, and stood on her tiptoes to whisper into my ear, “Madam, I’m afraid — ”

“I know,” I said, “but we knew she would only be a step behind — we have to go,” but she shook her head frantically, leaned closer, and hissed:

“What is this thief going to do to us when she finds out there isn’t any consortium?”

My first, absurd impulse was to laugh, and I had to clap my hand over my mouth to stifle it. When I had myself under control, I shook my head, and bent to whisper back: “Zorione, how can it be worse than what would have happened if we hadn’t told her that there was?”

She let me go, then, her face pinched with worry. I wished I knew what to say to her — but I had a week to find an answer, and here and now I made my way through sputtering wires and hissing pipes through the little hallway where the smuggler had disappeared.

I found her in a worn chair at what I presumed to be the ship’s only control panel, laid out in red lights before a dark viewscreen not four handspans wide. “How long until we’re out of the atmosphere?” I said.

“It’ll take as long as it takes,” said the smuggler. “If you have any service complaints, you’ve got three guesses who you can complain to.”

Three guesses seemed excessive, but it was more munificence than I had been offered in months. “If I stand here behind you,” I said, “will I be in your way?”

“You’re in my way wherever you are,” she said, and shoved a lever forward, and beneath us the engines coughed irritably to life. “Don’t go into the back, it’s full of Szayeti falcon jars. Eighteenth dynasty.”

I would remember that. I let it settle to the floor of my mind for now, though, and tucked myself into what little space there was behind the smuggler’s chair. We had begun our journey back across the water, now, bouncing over the flickering waves. The spray threw rainbows around us, so bright I found myself blinking and missed our arrival at the launch spot entirely, and my first notice that we had begun to rise into the air was a hum in my ears, low and then louder — and then a pain in my head, as sharp as if someone had clapped their hands to my ears and squeezed. The smuggler was mouthing something — I thought it was here we go —

— and then the sky was fading, blue into a pale colorlessness, and the ocean was shrinking below us, dotted by scudding clouds. The floor of the ship shook, then coughed. My ears popped.

“Simple part done,” said the smuggler. I was beginning to believe she liked having someone to talk to.

That, at least, I knew how to indulge. “Simple part?” I said, as bewildered as if I did not already know the answer. “What comes next?”

“That,” said the smuggler, pointing with grim satisfaction. I allowed myself a moment of pride — it had been excellent timing — and looked past her pointing finger to where the Ceian-bought warship sat black and seething like an anthill in the centre of my sky.

“We can’t answer a royal customs holo,” I said, making myself sound surprised.

“Wasn’t planning to,” said the smuggler. “Primitive little fucks already gave the queen my face. Three decades ago, I flew from here to Muntiru and back through twenty ports without telling any man my name. Now every asteroid twenty feet across is full of barbarians in blue, asking for the order of every gene my mother gave me.” She paused. “Wonder whose fault that is.”

It took much faith to attribute that kind of influence to any Oracle, let alone the Oracle she meant. But faith, unlike warships, had never been in short supply on Szayet.

“What will we do?” I said. “Speed through the army’s radar?”

“Better,” said the smuggler. “We outweave it. Hold on.”

That was the only warning I got. In the back, I could hear Zorione yelp as the ship spun like a top, suddenly and violently. The smuggler shoved a lever forward, yanked it to the left, and pushed three sliders on the control board up to their highest positions. A holo had sprung to life on the dashboard, a glittering spiderweb of yellow lines delineated by a wide black curve at their edge. Within it was a single white dot: our ship, I guessed, and the edge of the atmosphere.

“What’s that?” I said, anyway, and let the smuggler explain. She liked explaining, and it distracted me, which I knew after only a few seconds I would badly need. Flying with the smuggler was not unlike being a piece of soap dropped in the bath. She might have lost control of the ship entirely and I would never have known the difference, except for the unwavering fierceness of her smile. “How many times have you done this?” I attempted to ask through my rattling teeth as we swiveled and plummeted through empty air.

“At least twice!” she said, with malicious cheer.

It was difficult to tell when we passed the warship. Certainly the smuggler did not seem to know. I think she must have thought that, were I sufficiently bumped and jolted, I would give up and go join my nursemaid in the back, but I hung on stubbornly to the back of her chair, and stared from the control panel to the viewscreen to the holo and back again, matching each to each in my mind. It was an old trick I had, when fighting off illness or pain or plain misery, to focus on something at which I felt very stupid, and learn each detail as if it were another tongue. At other times it had served me well. Now, hungry and tired and nauseous all at once, it was more difficult, and by the time the ship turned once final time and settled at last into stillness, I was clinging to the smuggler’s chair as if it were my father alive again.

The smuggler smirked. “Twenty minutes,” she said. “New record. Hey,” she added in Szayeti, mostly to herself, “maybe she carries good luck after all.”

“I try to,” I said, in the same language, and caught the flicker of her first true smile. Below us, I could see the broad white edge of the planet, beginning to shrink against the darkness. I had seen it from this distance only once before in my life.

My people are a people of prophecy. Long before Alekso Undying came from old Sintia to our shores, long before my ten-times-great-grandfather carried His body weeping from the palace at Kutayet to the tomb where I grew up, my people spoke with the voices of serpents and lions, falcons and foxes, who roamed this world and who saw the future written in blood. The people then said what was, what is, and what will be; and though Alekso’s beloved and his descendants are their rulers now, and though they have had no god but their conqueror for three hundred years, they have not forgotten that they once told the future as freely as any queen. They never will.

The Queen of Szayet had prophesied, these last six months, that she was the only and rightful bearer of the Pearl of the Dead. She had prophesied herself the heir to the voice of Alekso our conqueror, the Undying who had died those centuries ago. She had prophesied her words were His words, and her words were the future, and that there was no future in them for Altagracia Caviro Patramata, father-beloved lady of Alectelo, seeker of the God and friend to the people, her only rival, her only enemy, her only and her best-beloved sister.

As the rust-green coin of Szayet receded before me, and the night crept in from every corner of the viewscreen, I leaned across the smuggler’s shoulder and pressed my fingers to the glass as I had to the arch at the harbour, and I whispered: “I will see you again.”

My sister had called me a liar today.

I am a liar, of course. But I meant to be a prophet, too.

Chapter Two — Ceirran

I had loved Quinha, more’s the trouble.

In the whole empire of Ceiao, for all its rabble and reputation, there’s only a fistful of citizens who have the born-or-bred true talent of a military general. Fewer with the charisma and the money to handle the populace, and fewer still who have any head for politic, and only a sprinkling, only enough for me to count on the fingers of my good right hand, are that rarest of things: a damn fine pilot. Quinha had been all of these, and a friend beside. I’d fought with her, and plotted with her. I’d cared for her. I hadn’t wanted to kill her.

Nevertheless.

She was coming up the meteor bank when her ship slipped into our sights: an imperial dreadnought twenty klicks wide, blooming on our radar screens as a mass of shifting yellows and reds. In the darkness of the accretion-tide she was hardly visible. If I’d been in my fighter I might have caught her, and picked off her cannons, one by one, and my fingers itched for the controls. But those days were gone and had been for many years, and I had my governorship to think of, and my dignity besides.

“Let me at her,” said Ana, who had neither. She was sprawled in a curved white chair at my right hand. She liked that sort of thing, Ana did. If she had ever been able to find the patience for subtlety, she wouldn’t have looked for it.

I considered the thought. Ana was no ace, but she was a quick draw and a vicious brute in battle, and it paid to indulge her, more often than not. But I shook my head in the end.

“I want her pinned to a planet,” I said, “and coming out ground-fighting. Bring the soldiers their force-shields, and pull around Laureathan to port. We’ll drive her up the bank towards the star-well.”

“Like conquerors we’ll do it,” said Ana. “Bring her corpse before us to the city gates.”

That wasn’t why. Quinha’s ship was borrowed, a colony-made pirate thing, but I feared her guns. If I had no choice but to fight her in open space, I’d send in a dozen fair-size destroyers, and do her damage enough to make her hesitate at coming within our cannon range. For now, though, there was choice, and I would have been a fool not to notice it. And there was another reason beside this, which Ana would have had no stomach to hear. “Yes,” I said, anyway. “She’ll try to find safe harbour on some near planet. We’ll carry her in the brig for the home journey.”

I had not known, at the time, what planet she would seek out. Even had I known, would I have cared? The hand of the Empire reaches far and wide, from old Cherekku’s stone mazes to the sulfide-storms of Madinabia, and I had not been to this arm of the galaxy since my childhood. We make a point, in Ceiao, not to be overcome by decadence. Even the name of Alekso of Sintia means little to us.

It meant little to me, in any case, at the time.

We surged after her. It was a great ship that I was riding, built under my eye at Ceiao’s own river-docks by a thousand trained workmen. Quinha’s wasn’t, and she knew it: we could see her struggling to dart and weave among the asteroid storms, her aching-slow banks and turns up the gravity curves. If she’d charmed the builders, or bribed the navy, or besieged the dockyards, or had her men installed among the magistrates — but she hadn’t. She hadn’t, and I had, and she had lost Ceiao, and I had won the war.

It made me ashamed to watch her fly. She was the one who had taught me, all those years ago, never to respect a commander whose fighting begins on the battlefield.

When she gunned her engines I hesitated. This was her corner of local space, and she knew it like the back of her hand. She might have been leading me into the path of a comet, or some trick of local gravity that would have sent half the fleet tumbling into a newborn star. But her dreadnought was shrinking in our sights, and Ana had risen from her seat and was pacing the viewscreen like a lion.

“Chase her,” I said, and shut my eyes as the great warship shuddered underneath me. Betting against Quinha’s long experience had failed me in the Merchant’s Council once. Betting against it a second time on the battlefield had won me a city. Best of three, as they said in Ceiao, made fortune.

I needn’t have worried.

The system rose up in our viewscreen all at once. It was an old star we were looking at — life-bearing, naturally, but reddening and rusted around the edges. There were only a few planets, idly flung out beside it at haphazard angles. Nearly all were ringed; only one, a little blue-green thing with a patchwork of cloud atop its surface, was surrounded by a sprinkling of moons, and even they were peculiar and knobbled, jagged at odd edges. I thought of a rogue planet ploughing through the orbit-path, until Captain Galvão Orcadan said behind me: “Szayet, sir.”

Szayet! I exhaled. “Prepare the rafts,” I said, and a few lieutenants sprang into life and disappeared down the ladders. “Get ahead of her, if you can, shunt her towards Medveyet — but if you can’t, press her in hard. The less time she has to disembark the better. She’s got ocean-ships in that hold, and provisions for weeks. I don’t want her hiding on the water out there.”

“She’ll need to make landfall, sir,” said Galvão, “or try to exit the atmosphere again, and we’re sure to see if she does. She can hide, but she can’t hide for long. We may not need to chase her down at all.” His voice crept up at the end, uncertain.

“I have no intention of letting every cynic in Ceiao watch me spend thirty days blockading the richest treasury in the Swordbelt Arm,” I said.

Galvão subsided at once. He was right, of course, and if I could, I would have told him so. But there was a reason I wanted to meet Quinha planetside, and it was a reason I had kept from Ana.

There was a veneer of ships overlaying the planet, thicker than I had expected. If I hadn’t known better I might have thought she had steered us into a trap after all — they were our make, each of them, good Ceian steel gunboats and galleons and blue destroyers dodging in and out of the ports like flies — but they were the local government’s, of course. Bought at a premium, most likely. I might even have sold some of them myself, back in my magistrate days.

Nevertheless I held up a hand, and the ship slowed and pulled up into a reluctant orbit. Quinha was barreling forward, of course, past the gunners, towards the thick, drifting air of the planet. The ships made no move to stop her as she grew smaller and smaller, like dust, and finally popped out of eyesight. Still I watched, and still I waited, and when Galvão grew restless and said “Commander Ceirran, you said — ” I held up a hand again.

“I know,” I said. “One moment more.”

Ana had gone dead still. Only her eyes were moving: from me to the viewscreen, from the viewscreen to me, her head cocked like a dog that had scented prey. I caught her gaze and held it, telling her: Wait, and: Yes, and her lips parted slightly — There it was. I took a step forward, involuntary, and Ana’s head whipped round: a Szayeti destroyer, peeled away from the nearest warship, was dropping like a stone towards the planet.

“Is it — ” said Galvão.

“It is,” I said. “They’re going after her. Someone find the lieutenants and tell them to hold our ships.”

Ana said nothing. She followed me back to my quarters, though, as I had known she would do, and when we arrived she shut the door behind her and threw herself into the chair across from my desk.

“Fortune’s tits,” she said. “You’ll give up a prize we’ve chased down half this spiral arm? And for what — politic?”

“Will I?” I said mildly, easing myself down across from her.

“She’ll raise an army,” said Ana, “and stretch out this war for another three months, and send half my men to the void, and they will rake you over the coals at home, and I’ll be stuck on the inside of a cruiser, poking at radar screens and driving you mad with complaining. Not a chance! Let me at her, and to hell with Szayeti sovereignty — what good has it ever done them anyway?”

“Your grasp of foreign policy is remarkable,” I said. “Tell me, what is your opinion of the Oracle of Szayet?”

“The girl?” said Ana. “I’ll tell you this much, I’d have bet my captain’s pin she’d be a poor strategist, but it turns out I was wrong. Another reason you should let me take twenty men and — yes, all right. Good-looking. Parochial. A bit of a complainer, to my mind. Young to be queen. Hope she’s more careful about eating rotten meat than her father was. Why?”

“I met her father, once,” I said, “but never her.”

“Well, I never met her either,” said Ana. “What of it?”

“I know,” I said, and picked up a tablet pen and rolled it over my fingers thoughtfully, knuckle to knuckle. “Has Quinha?”

That stopped Ana in her tracks. She leaned back in her chair and looked at me with narrowed eyes. “You think she hasn’t,” she said. “You think Quinha can’t manage her?”

“I am not,” I said, “entirely sure that Quinha knows what she is managing.”

“How old is she, fourteen?” said Ana, who knew very well Casimiro Caviro Faifisto’s daughters were only a few years younger than she. “That’d be old enough to go to war at home. How childish can she be?”

Back the tablet pen went, over the same four knuckles. “Are you in debt, Anita?” I said.

“That’s a personal question,” said Ana, and when I looked at her, “Yes, and you know the amount to the centono.”

“So is Szayet,” I said. “By several orders of magnitude more than you, I hope. From simply buying the Ceian ships they needed to defend themselves, at first, and then from buying Ceian weapons, and then her advice, and then her aid. Faifisto nearly tripled the debts in his lifetime, but he inherited them from his aunt, who inherited them from her mother, who inherited them from her grandfather, and he used Szayet itself as collateral against them when he put down a civil war.” I tapped the tablet pen on my desk, and it woke into a shivering sea of maps and paperwork and waiting holos. “Quinha bought the bulk of them,” I said, “not long after we met.”

Ana stared a moment, then swore.

“Then you will give up the prize,” she said. “She won’t need to raise an army — the queen will raise one for her! What in the world are you thinking?”

“I am thinking,” I said, “about diplomacy. Do you have your dress uniform?”

Excerpt from Emery Robin’s The Stars Undying reprinted by permission of Orbit.

The Stars Undying is currently available for preorder and will be released on November 8.