Move over monotremes and the range of rodents known to glow: over one hundred other furry creatures do, too, new research shows, vastly increasing the number of mammals known to show the spooky trait.

A team of researchers recently documented fluorescence in cats as well as a slate of 124 other mammalian species, indicating that the class of vertebrates still has a few tricks up its collective sleeve. Their research is published in Royal Society Open Science.

The technical term for this glow is a superpower biofluorescence. Biofluorescence occurs when animals take in ultraviolet light and emit the energy in any number of colours of the electromagnetic spectrum. Biofluorescence is different from bioluminescence, the slightly more common term that describes an organism’s glow that comes from reactions within the critter. Biofluorescence only occurs because the animal is exposed to an external light source.

In 2020, a different team of researchers revealed that the platypus—the duck-billed, egg-laying, venomous swimmer of Australia—glows a bluish-green under unfiltered UV light as well as under UV light with a yellow filter. The following year, springhares—a rodent built like a kangaroo that’s native to Southern Africa—was found to glow in an eerie red when exposed to UV light.

When the platypus was found to be biofluorescent, it was just the third mammal to join that club following opossums and flying squirrels. But the new findings increase the number of mammals known to glow by a significant margin.

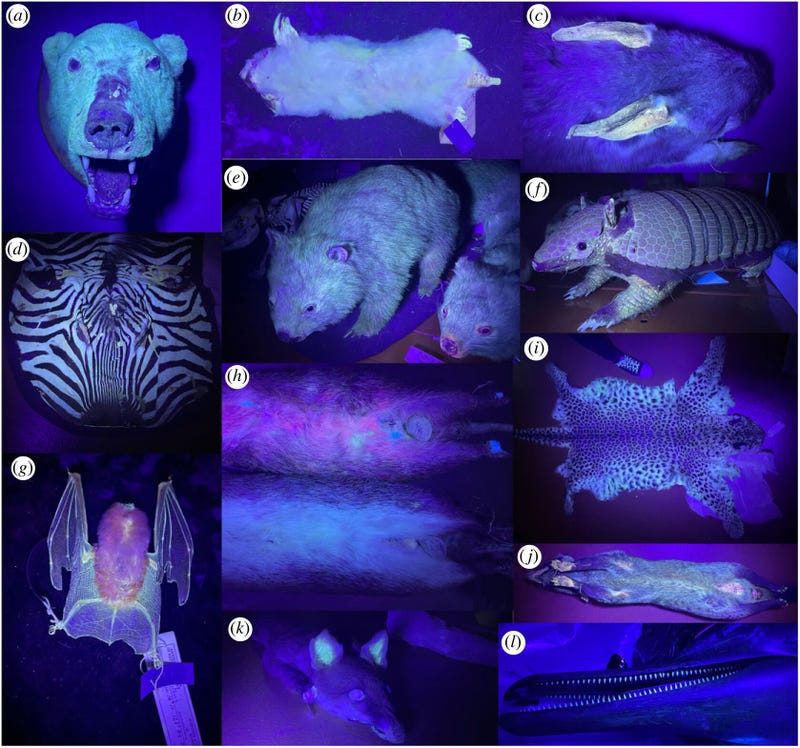

The 125 mammal species that fluoresced were studied via specimens at the Western Australia Museum’s collection. Some of the biofluorescent mammals included in the research were the bilby, six-banded armadillo, leopard, red fox, dwarf spinner dolphin, polar bear, and the domestic cat.

In some animals, like the cat, only some of the creature’s fur appeared to glow—in the cat’s case, white fur but not dark fur. The team found that white and light-coloured fur was fluorescent in 107 out of the 125 species, and pigmented claws glowed in 68 out of the 125 species.

The researchers wanted to know if fluorescence was more typical in nocturnal species than diurnal ones. “We ran an analysis to correlate the amount of fluorescence recorded in our study with ecological traits such as nocturnality, diet, and locomotion,” said Kenny Travouillon, the museum’s curator of mammalogy, in a museum release. “In the end, we found that many diurnal mammals also glow, but nocturnal mammals glow a bit more.”

Travouillon warned nature lovers not to shine a UV light to spot glowing mammals at night. “Remember that UV light can damage their eyesight, and you should take a red light to do your spotlighting instead,” he said. Should you actually go look for glowing mammals in the dark, let’s hope you find a cat and not a polar bear.