A deep-sea scientific expedition off the coast of Mexico has uncovered some weird stuff on the ocean floor, including six possibly newly discovered animal species of arrow worms, crustaceans, mollusks, and roundworms. The research crew also found striking hydrothermal vents fuelled by geologic activity beneath the seafloor.

The expedition was led by a multidisciplinary group of scientists from Mexico and the U.S. and conducted over the course of 33 days off the coast of the Mexican state of Baja in the Gulf of California. Researchers used the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s research vessel and released images this week that reveal some of the secrets of deep-sea ocean life.

You Can Thank a Robot the Size of a Minivan

The Gulf of California averages roughly 1 kilometre in depth, though it plunges much deeper in other locations. The Gulf is a relatively young body of water, formed just around 12.5 million years ago when the Baja Peninsula began to break away from the rest of the continent. The Gulf is also where several tectonic plates have split apart, forming four deep ocean basins that contain fascinating and little-studied features and lifeforms.

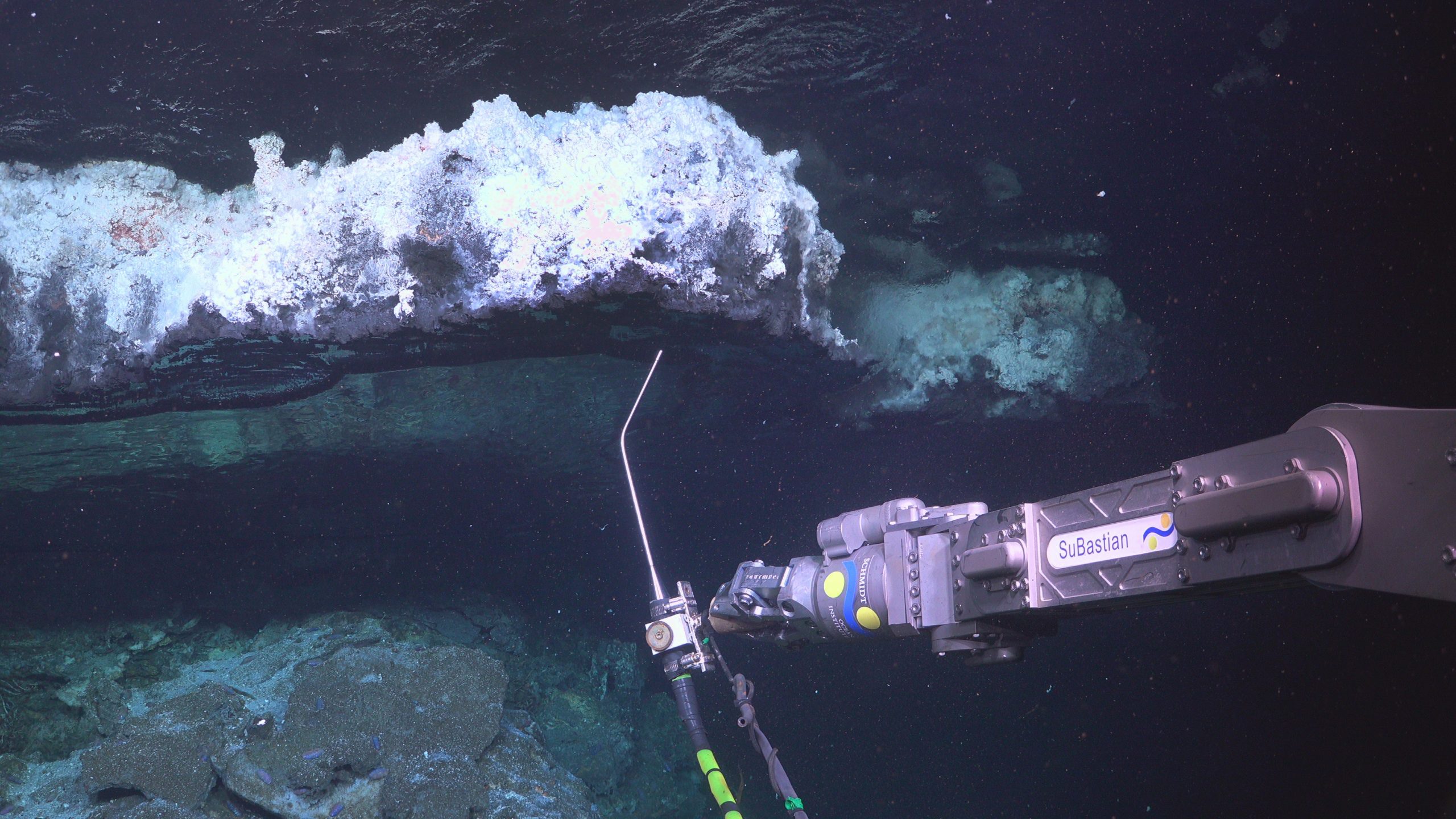

To explore what was down there, researchers used a remote operated vehicle (ROV) that helped map the ocean floor, take photos and samples, and deploy other scientific equipment. This robot, which is the size of a minivan, can dive up to 4.500 kilometres underwater.

‘This Is the Frontier’

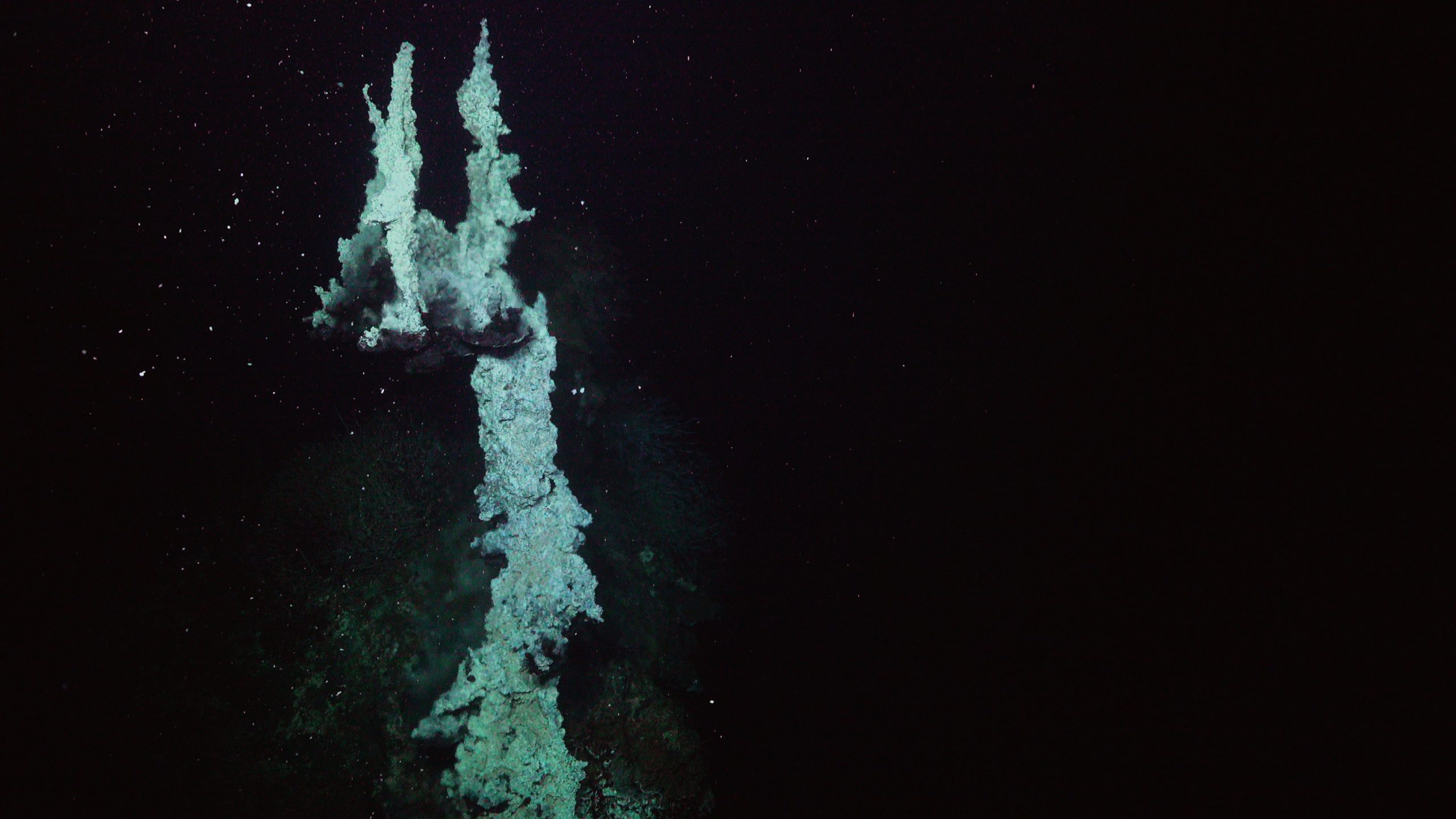

One of the primary aims of the expedition was to check out what’s known as hydrothermal vents — fissures on the ocean’s floor that expel warm, mineral-filled water and provide a home to all sorts of fascinating creatures and lifeforms. Hydrothermal vents were only first documented in the late 1970s, so we’re still learning a lot about how they work and the life inside them, as well as discovering new vent locations around the world.

The hydrothermal vents in the Gulf of California are unique from others observed elsewhere in the world, thanks in part to the heavy sediment levels that help change the chemical makeup of the water.

“The deep ocean is still one of the least explored frontiers in the solar system,” said Robert Zierenberg, one of the expedition’s lead researchers and an emeritus professor of geology in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the University of California, Davis. “Maps of our planet are not as detailed as those of Mercury, Venus, Mars, or the moon, because it is hard to map underwater. This is the frontier.”

Underwater, Upside-Down Lakes

The vent field the team explored was near one that they’d first documented in 2018, which they named JaichaMaa ‘ja’ag, an indigenous Yuman word referring to liquid metal. The name is thanks to one of the vent’s features: an underwater cave where hot fluid gathered at the top, creating a mirror-like effect researchers describe as “an upside-down lake.”

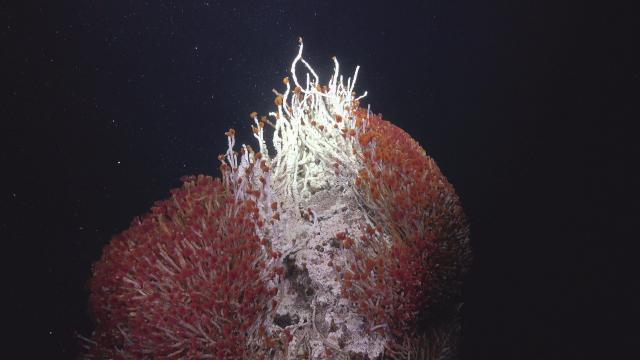

On this trip, they documented several more vents in the area, measuring water temperatures up to 287 degrees Celsius. One they named Maija awi after a water serpent in the creation myth of the Kumiai people who live in the Baja area. Another group of vents the researchers named ’Melsuu, a Yuman word for the colour blue, which is a reference to how many striking blue worms lived in the vents.

Glittery ‘Elvis Worms’

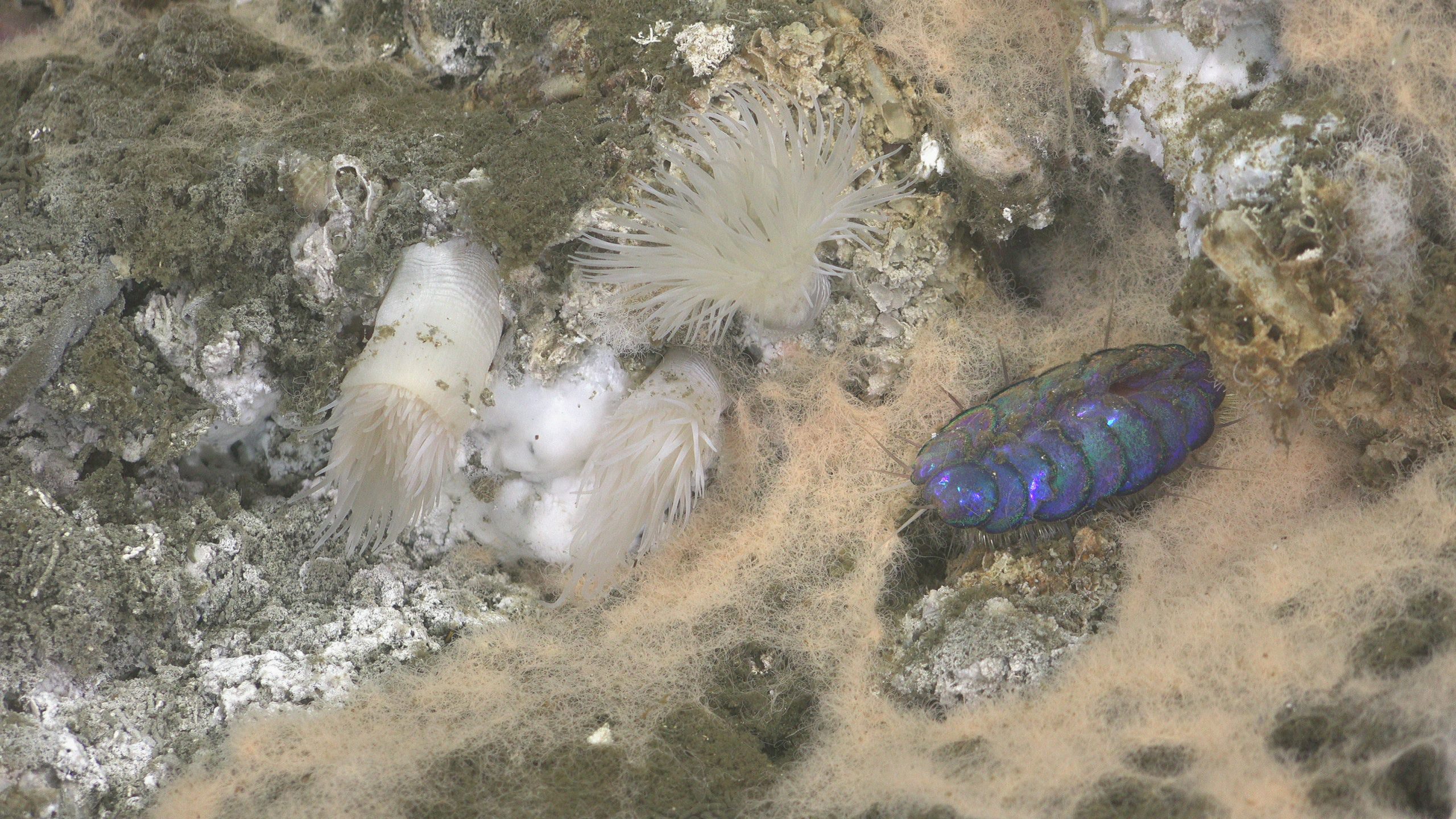

About those worms — they’re what’s known as Peinaleopolynoe orphanae scale worm, which (adorably) means “hungry scale worms” in Greek. These types of worms, also referred to as “glitter worms” due to their colourful appearance, were only officially documented last year. But the researchers have an even more incredible moniker for them.

“Our nickname for them was Elvis worms because they look like sequins on an Elvis jumpsuit,” Scripps marine biologist and study researcher Greg Rouse told Inside Science last year. These worms apparently will jump at any chance for a fight. Video taken from the 2018 Schmidt expedition shows blue scale worms engaged in a weird aggressive dance with each other, with one seemingly trying to take a bite out of the other.

Where Worms Hang Out

This expedition helped researchers find out more about these kinds of worms and other species, as well as where they prefer to live among the vents documented.

“There appear to be differences in which vent animals dominate these different hydrothermal features,” Victoria Orphan, one of the expedition’s lead researchers, said in a press release. “The sites to the south had the highest density of blue scale worms, while others appeared to be more densely colonised by chemosynthetic anemones or tube worms.”