For the past three months, a mysterious hacker gang has been giving Silicon Valley a migraine of epic proportions. LAPSUS$, a band of cybercriminals with unorthodox techniques and a flare for the dramatic, has been on a white hot streak — lining tech companies up and knocking em’ down like bowling pins.

The gang’s targets are big. Microsoft, Samsung, Nvidia, Ubisoft, and, most recently, identity verification firm Okta, have all been smote. Worse, in nearly all these cases, LAPSUS$ wormed its way deep into these corporations’ networks, where it then stole pieces of source code — the digital DNA of proprietary software. After that, the gang almost always leaked the code all over the internet, embarrassing the victim and spilling company secrets into the ether.

The group’s acumen has led it into the innermost sanctums of multi-billion dollar companies, but some security researchers say that LAPSUS$ may ultimately be composed less of hardened cybercriminals than undisciplined amateurs. A bunch of them are allegedly children. On Thursday, British authorities announced the arrest of seven people said to be connected to the gang. Authorities revealed that the unidentified suspects ranged in age from 16 to 21. The ringleader of the gang is reputed to be a 16-year-old British kid from Oxford. That hacker, who is said to go by the pseudonym “White,” appears to have recently had his identity leaked to the internet by a rival cybercrime faction. In short: after a string of victories and a lot of notoriety, things don’t appear to be going particularly well for LAPSUS$.

“Unlike most activity groups that stay under the radar…[LAPSUS$] doesn’t seem to cover its tracks,” said researchers with Microsoft’s Threat Intelligence Centre, in a recent blog post. “They go as far as announcing their attacks on social media or advertising their intent to buy credentials from employees of target organisations…[the gang] also uses several tactics that are less frequently used by other threat actors tracked by Microsoft.” Yet it’s those very tactics that make the gang so fascinating.

The ransomware gang that wasn’t

Before going on to hack some of Silicon Valley’s biggest companies, LAPSUS$ spent January of 2022 pulling a whole lot of juvenile cybercrime stunts — the likes of which seemed less about making money than having anarchic fun. In one of its first hacks of the year, for instance, the gang attacked a Brazilian car rental company, redirecting the business’ homepage to a porn website for several hours. During another incident, the gang took over a Portuguese newspaper’s verified Twitter account and tweeted: “LAPSUS$ IS OFFICIALLY THE NEW PRESIDENT OF PORTUGAL.”

Early reporting on LAPSUS$ attempted to categorise the group as a “ransomware gang,” partially due to its habit of leaking stolen data — as ransomware gangs are wont to do. Superficially, it might have appeared to be one, but there was just one problem: LAPSUS$ never actually used ransomware.

The gang has operated purely via an extortionist model, eschewing malware altogether. Instead of encrypting victims’ data, LAPSUS$ just steals it — then threatens to leak it if its ransom isn’t paid. It’s an odd, clumsy variation on the ransomware industry’s double extortion model — which uses the twin-threats of data encryption and leakage to goad victims into paying. In general, most ransomware gangs operate like shadow versions of typical corporations — deploying fairly organised and sophisticated digital machinery towards theft and extortion.

Conversely, LAPSUS$ has operated like a dysfunctional startup. It has, in some cases, lacked the discipline to even ask for a ransom — opting instead to skip a financial demand and just leak the hacked data for the hell of it. Microsoft security researchers have referred to this style as a “pure extortion and destruction model,” a turn of phrase that aptly describes the group’s chaotic and not altogether effective modus operandi.

Wreaking mayhem

One area where LAPSUS$ has clearly been successful is intrusion — i.e., its ability to get inside networks and systems. The group has leveraged a number of well-known strategies, including the use of a password-stealing malware called “Redline,” a variety of social engineering ploys, and the purchase of account credentials and session tokens on darknet forums. At the same time, the gang has frequently courted insiders from target companies, attempting to poach them via what amount to online job posting ads. In one case, the alleged leader of the group offered employees at Verizon and AT&T as much as $US20,000 ($27,764) a week to defect to his criminal operation and conduct “inside jobs.”

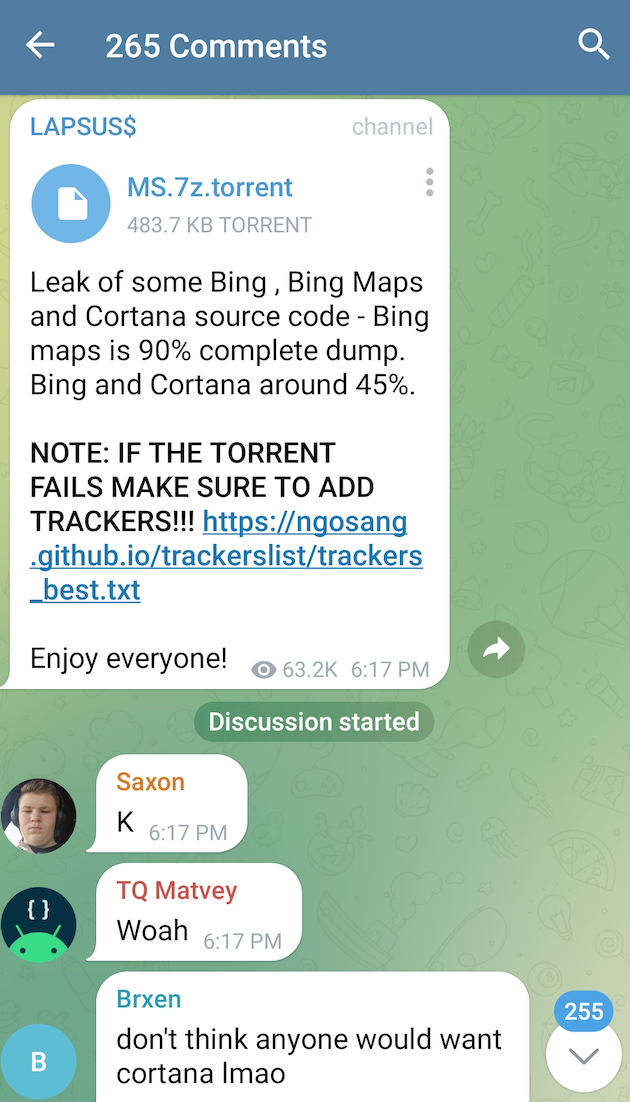

LAPSUS$’ varied methods of pwning its targets have been remarkably successful. Its hack of Microsoft, for instance, is believed to have compromised a wealth of data, including 90 per cent of the source code for the search engine Bing, as well as nearly half of the source code for Bing Maps and the virtual assistant Cortana. The gang’s attack on Okta, meanwhile, may prove to have implications for companies beyond the identity verification firm itself. Because Okta sells its security services to thousands of other companies, a compromise of its systems has security implications for its clients, too. In an update on Wednesday, Okta admitted that the data of as many as 366 of its clients had been potentially affected by the recent LAPSUS$ attack.

Seeking notoriety

Another indication of the gang’s flashy but potentially reckless tendencies lies in its unique leak vector. LAPSUS$ uses the semi-encrypted chat app Telegram — not typical of most cybercrime gangs. Most ransomware hackers set up their own “leak sites” where they can curate hacked material and threaten to release more if their victim doesn’t pay. The sites are typically sparse and controlled environments.

LAPSUS$, meanwhile, has wielded Telegram and other social media accounts as a kind of megaphone — a strategy that’s allowed it to cultivate a louder, more interactive relationship with the public. The gang currently has some 48,000 Telegram followers and actively encourages its onlookers to comment on leaks, correspond with members via email, and generally follow along with the adventures in hacking.

This behaviour would seem to reveal that LAPSUS$ enjoys attention — potentially even more than they like money, but probably less than they like hacking. That might actually be the group’s problem: like a lot of rookie criminals, they seem more concerned with adrenaline rushes and the limelight than they are with running an effective money-making operation.

Amateur hour

Cybersecurity analysts who spoke to Gizmodo agree that, despite the list of impressive notches on its belt and its successful intrusion techniques, LAPSUS$ may not run the tightest ship. That is, the gang may be better at hacking than at running a criminal business (this would make a certain amount of sense of the gang is allegedly a bunch of kids). Brett Callow, a threat analyst for cybersecurity firm Emsisoft, said that some of the gang’s behaviour clearly shows a lack of efficiency and organisation.

“Had the attacks been carried by a more organised cybercrime operation or a state-backed actor, the outcome could have been much worse,” Callow said in an email to Gizmodo. “That’s not to downplay the threat which groups like LAPSUS$ can represent. The fact that their motivations aren’t necessarily as clearly defined as other cybercrime operations can make them harder to deal with.”

Similarly, Motherboard journalist Joseph Cox has written about his encounters with the gang — the likes of which range from the bizarre to the outright comical. To hear Cox tell it, LAPSUS$ haplessly reached out to him for help after it hacked EA Games last summer. The gang, which was unsure of how to ask EA for a ransom, seemed to think that because Cox was a journalist he could liaise with the company and “act as a conduit” for the gang’s financial demands.

Other analysts agree that LAPSUS$ doesn’t really know how to secure a payout — and may not, in fact, even be interested in one. “LAPSUS$ has a history of making unrealistic demands in exchange for its stolen data,” threat researchers with SecurityScorecard recently wrote in a blog post.

“LAPSUS$ doesn’t seem to be able to determine an appropriate ransom amount for the data it has stolen, nor does it appear to give its victims much time to negotiate a payment in exchange for not leaking information,” they added, explaining that, in reality, the group “may not be financially motivated” at all. LAPSUS$ may be sowing chaos for the thrill of it and “making demands knowing that victims won’t pay, so they can then gain attention and infamy by leaking data from high profile companies,” the researchers wrote.

Doxxed and reported

If the members of LAPSUS$ wanted infamy, they certainly seem to be headed for it. The gang’s happy days of exultant mayhem may now be in the rearview, as law enforcement increasingly closes in. Aside from the rash of arrests that took place Thursday, the gang’s alleged leader also appears to have another problem on his hands: getting doxxed by a rival cybercrime faction.

The hacker in question, who goes by numerous online pseudonyms including “White,” “Oklaqq,” and “Breachbase,” is alleged to be a 16-year-old kid who lives at home with his mum near Oxford, England. BBC reports that he also has autism and attends a special education school in Oxford. In a brief interview, the suspect’s father apparently admitted that his son spent “a lot of time on the computer” but “thought he was playing games” or something. In January, the alleged hacker’s rivals released what they said were his real name and other identifying details via Doxbin, a controversial website that is specifically used to leak personal details about people. In a post on the site, the doxxers said “White” owned over 300 Bitcoins, which would amount to a net worth of nearly $US14 ($19) million. They called LAPSUS$ a “wannabe ransomware group.”

According to Allison Nixon, chief research officer of cybersecurity firm Unit 221B, “White” was doxxed due to his prior business relationship with the operators of Doxbin. When Gizmodo asked her about the purported leak of the hacker’s identity, Nixon affirmed that a “rival criminal group” had ended up “finding and publishing” the suspect’s personal information. According to Nixon, Doxbin was actually purchased by “White” at some point, but he ended up being an ineffective administrator. As apparent revenge for letting the site “fall into neglect,” the former owners regained control of Doxbin, then decided to dox “White” for his shoddy management practices, Nixon says.

Gizmodo has viewed screenshots of the Doxbin post, but we are not disclosing the details that purport to identify him.

Nixon also told Gizmodo that her company had been working with a number of other cybersecurity firms for the better part of a year to track the activities of “White,” and that, as early as mid-2021, they had uncovered the hacker’s real identity and subsequently reported him to police. It’s unclear whether law enforcement has been investigating the gang since that time or why it took so long for suspects to be arrested.